INTERVIEW WITH ERIC WASSERMAN

Author Bio:

Eric Wasserman was born and raised in Portland, Oregon where he attended Lewis & Clark College. He holds an MFA from

Emerson College and is now an Assistant Professor at The University of Akron, where he also teaches in the Northeast

Ohio Master of Fine Arts program in Creative Writing. He is the author of a collection of short stories, The Temporary Life

(La Questa Press, 2005). His short story, "He's No Sandy Koufax," won First Prize in the 13th Annual David Dornstein

Creative Writing Contest, and his work has appeared in or is forthcoming in many publications, including Glimmer Train,

Poets & Writers Magazine Online, Michigan Quarterly Review, Vermont Literary Review, and Istanbul Literary Review. His

story "Brothers" was the winner of the 2007 Cervená Barva Press Fiction Chapbook Prize. Eric has recently completed his

first novel, Celluloid Strangers. He lives in Ohio with his wife, Thea. Visit him at www.ericwasserman.com.

The room I write in:

I write in the back office of my apartment. It wasn't much until my incredible wife, Thea, decided I needed to make it my own.

I am surrounded by movie posters and books and mostly write on my Mac, although I do all editing by pen on printed manuscripts

(that's the real writing for me). To the right of my desk is an extra chair with a pillow for my cats to sit on and look out

the window, captivated by squirrels outside as I work. I am surrounded by pictures of those I love, both living and dead. And

I have a replica of Michelangelo's statue of Moses as inspiration for the new novel I am working on. I also have plenty of

file cabinets since I never through anything away that I write and always print out drafts, then more drafts, then even more

drafts, and drafts and drafts and drafts. I'm a multi-tasker, which my wife admires, but it drives her crazy when I am

writing with the music cranked up as loud as it will go (if we ever buy a house she's insisting on sound-proofing my

future office). I am not one of those people who can write in a coffee shop and I never write by hand (only edit by pen

on what's typed). I prefer having my known space, my apartment office. If I go to a coffee shop I am going to have a nice

time and enjoy good company and good talk. I am sure there are exceptions, but I get the impression that people who write

in public are in love with the idea of being a writer instead of embracing the writing life. I hope I am wrong about that.

For me, if you want to be a writer you need to be quite secure and content spending massive amounts of time by yourself

bringing your imagine worlds to life on the page. For me, that place is my home office. Besides, I can't bring my cats

to a coffee shop.

Some (I stress "some") of the writers who have influenced me and why?:

To be honest, I think writers are influenced by everything they read. In fact, I don't read to have my sensibility of the

world reaffirmed; I am struck more when I'm challenged by a different perspective. And I have probably been influenced just

as much by what I don't connect with because it shows me what I don't want to be doing as a writer. So, if I gave you a genuine

list it would be exhausting.

That said, I should say that if you had to simplify things, my greatest influences remain Salman Rushdie, Philip Roth and

Mikhail Bulgakov. All of these writers possess the "what if?" factor in their fiction. To be honest, I like minimalism in

doses but I've never seen the great attraction to it except for Carver and the few others in his top shelf class. I am looking

for possibility in fiction, and I am not a reader who needs completely grounded realism. I love hyper-sensitized realities in

which the author is pushing the world we know to the limit of believability to make a profound point. If you look at

Rushdie's The Satanic Verses, Roth's The Counterlife, and Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita they are all doing that.

Also, when you talk about influences a writer must look at writers and their body of work, not just individual gems.

I don't like everything these writers do, but holistically they all captivate me and I want to keep reading them because

I never know what I'm going to get as a reader. I can't say that for other writers. Also, I am somebody who appreciates

language because I think it matters just as much as story and Rushdie, Roth and Bulgakov all seem to be able to bend

language to their very will in ways that I am continually awed by. I would also like to say that there are specific books

by individual writers I continually go back to. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Ernest Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms,

Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried, and most recently Cormac McCarthy's The Road are very dear to me and probably

always will be.

How long have I've been writing fiction?

I'll place the number around fifteen years, if you are talking about being serious about it. I've always been a storyteller.

That's the kind of family I have. We thrive on stories and I have been making them up my entire life. But I would say that I

have been writing fiction seriously since the summer after my freshman year of college when I turned 19. That's when I began

writing my first novel that hopefully nobody will ever see. Since then it's been an integral part of my life. But the creative

impulse was set in me from birth; I've always had it.

Talk about your collection of short stories, The Temporary Life (La Questa Press, 2005).

The Temporary Life was always imagined as a collection. Even the stories written that didn't make it into the book were components

of a greater whole. I have always seen my work as part of a larger picture anyway. Occasionally I will write something isolated but

I always have a larger book project going. Even "Brothers" refused to remain self-contained, it eventually became my first novel, at

least the first novel I am proud enough to publish and not hide away in a drawer. The Temporary Life was actually conceived in the

summer of 1996. I took a writing workshop from Jordanian-American author Diana Abu-Jaber and the title story grew out of an exercise.

Before then I had completed a worthless 250 page novel manuscript and I was basically writing what I thought I should be writing

instead of what I wanted to put down. Naturally, I've been a great consumer of Jewish-American literature, but other than

Philip Roth I couldn't say I ever really saw myself in the majority of the Northeastern-centric fiction on Jewish themes,

and in fact I don't always see myself in Roth's worth either. However, when I mention him and Rushdie and Bulgakov as my

greatest influences it really is because they give me access to their worlds in a way that I can imagine myself living

within them, and that's rare.

The Temporary Life set out to present west coast Jewish-American life as I hadn't seen it in fiction. If you read a lot of

Jewish-American fiction you might get the impression that all American Jews are from New York City or New Jersey or Boston

and that our parents all retire to Florida. I don't know that world. I know a diverse west coast experience I was raised in

with cities such as Seattle, my hometown of Portland, Sand Francisco, and especially Los Angeles all having their own unique

Jewish-American sensibility and quirkiness. I wanted to capture that in the stories in The Temporary Life.

That said, while I am incredibly proud of the book, I would never write those stories today. Those are stories written by a

man in his twenties with a very different outlook on life. Today I am not the man who wrote those stories, but I am glad they

are there. Beyond the content of the stories, I can look at them now and see a young writer who was very hungry to make his

mark. And while some of the stories no longer hold up, they all have an immediacy and energy to them that I think only youth

can bring to fiction. I sort of miss that immediacy but I would never want to again be the writer who created those stories.

However, I recently did a short reading and decided to read the first few pages of one of the stories from the book and it was

nice to revisit those characters and feel that sense of being a writer in his twenties again. Now that I am in my thirties I

am hoping I can look at The Temporary Life the way I now look at one of my favorite movies, Richard Linklater's Before Sunrise.

I saw that movie when I was very young and said, "That's me!" Now I watch it and think in a bittersweet way of who I once was and

how that film reminds me of how I once saw the world and who I thought I was going to be.

Your short story, "He's No Sandy Koufax," won First Prize in the 13th Annual David Dornstein Creative Writing Contest.

Talk about this story.

That story is in fact the one I recently read the opening of to some colleagues and graduate students. Every self-respecting

writer has a baseball story in him, right? In the June 12, 1999 issue of Sports Illustrated there was an article titled

"The Left Arm of God" by Tom Verducci, who is one of the smartest sports writers in the country. The story really got me thinking

about a lot of things. Sports are very important in my family and I was honestly never any good at them. I just didn't have the

natural ability my brothers had except for modestly succeeding as a high school wrestler, but that's another story. I was so bad

at sports when I was a young boy that I actually pretended not to like them at all when I really did. Looking back, I guess it was

a defense mechanism of sorts; if I sucked at sports I could chalk it off to the fact that I supposedly just didn't like them. And

it worked because I had this incredible creative impulse whether it was Legos, or drama club, or music and movies.

When I was in college my father still had season tickets to the Portland Trailblazers. I didn't see my parents a lot but I remember

those games I would go to with my dad as being very special. It was when we really spent time together and when I think I finally

got to know him as an adult, get to know him as a person. That Verducci story made me think of how a lot of fathers I grew up around

talked about sports. My dad was raised in Los Angeles, and since Portland, Oregon didn't have a major league baseball team we kind

of routed for The Dodgers by default. I have always been interested in symbolism, how people see things for more than they really

are; what's under the surface. And I've always been interested in who people say their heroes are. And heroes change. When I was a

teenager my hero was probably Stephen Spielberg because I was obsessed with movies, but that's not the case any longer. I wanted to

write a story about how things can mean so much to certain people for very personal reasons but nothing to others. The main

character in "Koufax" is not my father. The story does have little bits of pieces of personal family history, but so far very

few have caught them. Mostly, I wanted to create a character who identifies so strongly with a public figure but resents that

others don't see the profound qualities in that figure that he does.

Your story, "Brothers," won the 2007 Červená Barva Press Fiction Chapbook Prize. It has just been released for publication.

Where did the story come from?

It is very loosely based on a true story my buddy John Zamparelli told me. The real story concerned two men who were not brothers

and it was an Italian-Catholic community in Boston, Medford in the fifties if I remember right. The story just really captivated me;

it was quite cinematic, especially the way John told it since he comes from a screenwriting background. I had just come back from

Los Angeles, where my family is originally from, and I have always been fascinated by history and how place becomes a part of our

own little personal histories. I essentially took the gist of John's story and instead made the men Jewish-Americans brothers in

the late 1940s. Aside from the general situation of a guy coming to tell another guy to step down from a job he's

always dreamed of, the story is completely fictional. Still, I like to think that the spirit of the original story

John told me is inherently there in the chapbook. Also, at the time, which was early 2001, I was writing these short

pieces of domestic fiction and I needed to do something different. I've always loved stories that blend genres.

I think of "Brothers" as a domestic story, but one that incorporates classic literary crime fiction elements in

the tradition of, say, Dashiell Hammett's The Maltese Falcon or Eric Knight's You Play the Black and the Red Comes up.

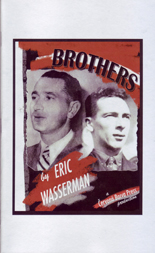

Your wife, Thea Ledendecker, a graphic designer, designed the chapbook cover, where did the photos come from?

The two men on the cover are my grandfathers. One of the nice things about publishing with a small press, beyond the personal

attention you get, is that most small press editors are generous and open to the ideas their writers have and will listen to

them. Sometimes those ideas are shot down, but they are at least respected. Thea came up with the basic concept for the cover

of my first book of short stories. I am a consumer of family history and love old pictures. I never expected that Thea would be

allowed to design the chapbook cover completely, I thought she would just be able to point the press in the direction I saw

fitting, as she did for my first book.

The process was very organic. I am not a visual artist, but I know what I like. I made some horrible pencil sketches of a

few different ideas for the cover. The most important part was that I really envisioned the cover of the chapbook being an

homage to those wonderful pulp B-picture cinema posters from the 1940s, the time period the story takes place in. Unfortunately,

movie poster art has become a lost craft because these days you can just use a still from the production. One might also notice

that the dialogue in the chapbook is quite different than the style in the stories from my previous book. I didn't want to mimic

the dialogue of those old movies, but I took it as my starting point, the terseness, the directness in the delivery. And since

the movies are so important to the story of the chapbook and the novel that eventually grew out of it, I thought the cover

should capture that. For my first book Thea used many of my old family photographs. For this one she took one of each of my

grandfathers from around the period. And since my two grandfather's didn't necessarily see the world eye-to-eye I got a kick

out of the idea of them sort of representing the two estranged brothers in the story. I was a little worried about using the

pictures of my grandfathers, but I sent my mother Thea's early mockup and she loved it.

Right now you are working on editing your novel, Celluloid Strangers.

How many pages is it now? You said you cut 100 pages. I don't want you to give away the story,

but could you talk about your writing process for this novel.

Actually, I just finished a new draft of the book yesterday to send off to my literary agent and it clocked in at

566 pages including the appendixes, which is intended as fun extra reading if anyone is interested. As I said, the

novel grew out of "Brothers." I had no idea I had a novel there, I thought I was just writing a short story, but it

became larger. There's always a danger of overwriting for me. For my wife, it's the danger of underwriting, not

layering the story. I layer far too much in my drafts. But I need to have everything on the page before I can do anything

with a story or its characters. The rough draft for "Next Year In Kona," the first story in my book of short fiction, was

over fifty pages long. I had to break it down to its bare essence and it was a gratifying experience. The manuscript for

Celluloid Strangers reached over 1,000 pages at a point. "Brothers" was probably a good third longer in its original

form than what it now is as a chapbook. And yes, it was overwritten, but I am the kind of writer who needs to go through that

process.

The novel required a lot of research, several years worth. Although several historic events and peoples are mentioned in it,

select dates and circumstances were altered or fictionalized for narrative purposes. Historic accuracy was never intention;

it's not a factual social or political history. It represents a hyper-sensitized interpretation of the "spirit" of the times

and events surrounding Old Hollywood and the House UN-American Activities Committee. The thing I always had to remember is

that the story is what matters. I could only use maybe 20% of my research. In fact, I am going to be leading a session in

November at Bowling Green State's Winter Wheat Writing Festival about how to incorporate research into a fictional narrative.

I'm really excited about the novel, but it's been a long, laborious experience writing it, and my head is already into my next

book. But that's how I work, while I am writing one book I am already taking notes for the next project.

You teach at The University of Akron as an Assistant Professor and in the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts program in

Creative Writing (NEOMFA). What do you try to teach your students about writing?

I think writing programs are really in a transitional moment and there is something exciting about that and I'm proud to be a

part of it. Creative Writing courses have unfortunately been seen as fluffy electives where students emote and there is little

craft analysis. I pride myself on giving students a grounded vocabulary with which they can deconstruct their own work. I am

not a literary theory wonk by any means, but a general understanding of it can save a writer years of trial and error that I

went through. Having a basic understanding of narrative space, content control and the delicate relationship between the author,

narrator and characters of a story will move students beyond this fallacy that they go off into the world and "live" then sit

down at a keyboard and everything pours out perfectly in one spit. Writing is labor, period. Revision is what I stress most,

probably because that's my real joy, where my stories truly come to life.

There are of course things that I can't teach students. I can't teach them discipline. I can encourage it, but I have given

up expecting them to all write from six to eight in the morning every day and cram in any spare time available, as I do. I

also can't teach them the blessings that failure provides, I just hope they can learn that on their own. The writers who have

even a modicum of success are the one who refuse to take no for an answer. If they are rejected by a journal, they send right

out to another one. If they have to accept that the story they are working on was a good effort and might not work the end,

they push on to write a better one. And they do this over and over and over again. Anybody can want to write, but the obsessive

need to do it is just there or it isn't.

And I try to explain to students that we're all in this together. Just the other day I got an e-mail from my literary agent

saying that my novel was rejected by a publisher I would have been happy to go with because, even though they admired it,

they could not conceive of a way to market the book. There's the crummy bottom line in publishing at work again. People studying

writing must learn to have faith in their own stories and not jump on trends because they think it's going to get them published.

Blacklisted screenwriter Lillian Hellman once said, "I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions."

That's a pretty good motto to live by as a writer. I've always written whatever I wanted to and probably always will. Sure,

I've missed some opportunities because of it, but I don't care. Writing is not like being a young actor and being forced to

take whatever roles you're offered and then beg for the next one in auditions.

Finally, I have to roll my eyes when I hear people telling writers to "find their voice." I have no idea what that's supposed

to mean, never have. The very act of writing itself means you have a voice and are using it, period. Shaping it, chipping away

the rough parts, that's another story, but the voice is already there in all of us simply by making the choice to put

words down.

What difficulties do you see in today's colleges and universities regarding writing classes and programs?

I think the debate over the validity of writing courses and writing programs has become incredibly juvenile. It serves nobody.

How about some constructiveness to make writing studies great; wouldn't that wonderful? Last year AWP invited a writer to speak

at its New York City convention who I once heard in a radio interview severely ridicule writing programs. Obviously AWP forgot

the "Program" part of its title. I heard from several people that this writer came for twenty minutes or so, was smug and

arrogant and left. The truth is that not everyone is made for a writing program and writing workshops. They work for some

people but not for others. Generally speaking, if you have experienced the process of disciplining yourself in some way,

whether that's sports or music or dance or whatever, you will do well in a writing workshop because you know that criticism

of your work is not personal, that you can understand what somebody is saying when they tell you, say, You're character

development is great but that there is little transformation in the person.

Some of the difficulties are in student preparation. Students certainly want to write but they don't necessarily want to read,

and that is the major problem. As it is apparent, I am obsessed with movies, but I read just as much, probably more. If you're

looking into writing programs, I highly suggest opting for one with a strong literature component. And ignore the ranking and

prestige of programs. Choose one that is right for you. Also, I think people should think twice about entering an MFA program

directly after finishing their undergraduate work. In some cases, it's definitely the right move, probably more so for poets

from what I have personally seen even though I can't be specific as to why, it's just a general observation. I took three

years off between college and graduate school and I know it was an asset because in those three years I had go-nowhere jobs

but I was constantly reading and writing. For a fiction writer, it's very difficult to create real and complex characters if

you don't yet know who you are as a person. But that's also an asset to young writers in classes and programs. You have so

many chances to try out different styles and approaches, like when you're young and are trying out different identities and

wardrobes until you know which one is the genuine you. I like to have my students look at just the first page of

F. Scott Fitzgerald's This Side of Paradise and compare it to the first page of The Great Gatsby. The novels are five years

apart but it's as if two different writers wrote them. Paradise is, as my friend Bob Pope would say, a beautiful mess of

a novel. But when you read Gatsby you are reading a novel written by a man who perhaps finally knew who he was as a person

and could then more intimately know who his characters were as people.

However, the biggest difficulty in classes and programs is that we need to be far more honest when it comes to the expectations

our students have. There is a trend of professionalizing writing programs and I tend to be in favor of it. Yes, I want students

to focus mainly on their creative work, but I don't want them to think that all they can use their degree for is a placemat.

Teaching should not be their only option as writers. I teach because I love it, my mother was a teacher after all. But

I would do something else if it wasn't for me. Not to shamelessly promote the program I am a part of, but the NEOMFA requires

students to do an internship and I am the internship director. Students are doing all sort of great things, including interning

at small presses or creating children's literacy activities.

In the end, I think the benefits of writing classes and programs far outweigh the difficulties. I don't really have use

for people who spend all their time trying to ridicule writing classes and programs, telling young writers they need to

take some pretentious vow of poverty and write at night after coming home from a crappy job to a crappy apartment.

Young writers have every right to want a good life, just like everyone else. And for two or three years, if they choose

to go to a graduate program, they will have the advantage of being surrounded by people who take their words seriously

and will have incredible access to accomplished writers in their field who can help them avoid mistakes I know it took me

years of trial and error to overcome.

What's the writing scene like in Northeast Ohio?

I've only been here a year but it's exciting. The scene here that I know mostly centers on the Northeast Ohio Master of

Fine Arts program in Creative Writing, otherwise known as the NEOMFA. And it's great. I miss living in Los Angeles. But

I don't miss poets and fiction writers being considered second-class wordsmiths. My wife used to cringe every time she told

somebody in L.A. she was working on a novel and almost without fail they would ask if she had ever though of writing a screenplay.

Of course, money was what they were really suggesting. I think the Northeast Ohio literary scene is incredibly supportive.

I thrive in that kind of environment. When I was in graduate school I always felt a slightly unhealthy competitiveness in

Boston's literary community even when I was loving it. What's great about the literary community here is that you see a lot

of young writers in their early careers that I guarantee you'll be hearing a lot more about in years to come. Poets like

Mary Biddinger, author of Prairie Fever, and Michael Dumanis, whose collection My Soviet Union is my favorite book of poetry

I've read in a long time, are right here in The Rustbelt. Then you have fiction writers like Christopher Barzak in Youngstown

who has a second novel with Bantam coming out this November, and Imad Rahman who has a novel out with FSG and who just took over

as the new director of the Cleveland State University Imagination Writing Festival. I am probably getting in trouble here because

I don't have time to name all the incredible writers in this area, including playwrights and those pursuing creative nonfiction.

But I mentioned the people I did specifically because they are all in their thirties and making their mark here. Naturally, there

are certain practical advantages to being in a big city to pursue the writing life but creative communities make themselves. I once

read Philip Roth saying something like, New York City is the center of publishing but not the center of writing,

and he was probably correct.

I like to think of the literary scene here in Northeast Ohio the way you look at The Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland.

That little town in Southern Oregon has one of the most respected Shakespeare festivals in the world! When I was at The Globe in

London in 1998 I mentioned I was from Oregon and the tour guide instantly brought up the festival. I want the literary scene here

to be like that. And it's already starting to be because along with these great young writers who are hungry there are so many

established writers who remain passionate about words and presenting them, whether it's to a room of five or fifty, whether it's

one poem or a full-length novel. It's what I've always looked for and now I have it.

Any last comments?

I'm a realist. I understand that technology has changed the world and books are not as important to most people as they used

to be. But I think those of us who cherish books can still do our little part. My nieces and nephews pretty much know that

Uncle Eric and Aunt Thea are going to give them books as gifts, and they usually like them. So if you are debating between

giving a child a book as a gift or a video game, please give the book. And if you have children or are close to children,

read to them before they go to bed. My parents did that for me. That's where it starts.

|