INTERVIEW WITH KEVIN GALLAGHER

Write a bio

Born in Boston the year MLK and RFK were killed, the year of the Tet Offensive, of Prague Spring, the Catonsville nine,

Mexico City student massacre, the Apollo missions and the White Album.

My best friend's grandma was Red Auerbach's secretary from 1961 til 2003 so I spent my childhood and then some

going to free Celtics games mid-court. I once wrote a poem that had a line that read

Freddy barged into Ricardo's barber shop

And said, "Make me look like Dino Radja!"

Unfortunately I can't find the rest of it.

At this very moment the Celtics-Lakers finals are taking just about all my time and energy. Frank O'Hara said poetry is

only sometimes better than the movies. It is never better than the Celtics and the Lakers in the finals!

Have a wonderful wife Kelly and son Theo. We lived in Charles Olson's Gloucester until the commute cut it short.

The photo of me is a fifty yards from his house. Now we're back in Boston, or Newton I should say.

Work? I'm a professor of international relations at Boston University where I teach courses on globalization, poverty,

and economic development, particularly in Mexico and Latin America. Poetry. From 1992 to 2003 I edited compost magazine

outta Jamaica Plain with great friends. Since then I've focused on my own poetry, publishing in mags like Partisan Review,

Harvard Review, Green Mountains Review, and Jacket. Isolate Flecks is my first book of poems, and soon Cy Gist will publish

my second, Looking for Lake Texcoco.

Describe the room you write in.

The poetry plays around in my head and a few days, weeks, months and sometimes years later I sit down and write it. Sometimes that's

on the couch, at my office, the subway, or in my bed. Poetry is not work for me it is part of a life. I'm the kind of poet where if

I had to sit down, roll up my sleeves and sit up straight it just wouldn't work. Though, a rare but fun Friday night is a glass of

Lagavulin with Arthur Rubinstein in the background and a book of poems. More often than not something gets conjured.

What are you working on now?

I'm currently editing a tribute to Denise Levertov for Jacket magazine. Jacket

(www.jacketmagazine.com) has to be the best on-line

magazine out there, and in the top 5 for print or web in my opinion. One of the great things they do is pay critical homage to

past poets. I've been struck by Levertov's work as of late. She was four or five different poets-in-one over a long career.

She started out as a lyric formalist, became one of the core Black Mountain poets (though she never taught there), was one of the

premier anti-Vietnam War poets, and then became one our greatest poets of nature and spirituality. I have affinities with all

those impulses and schools. As one will find in Isolate Flecks, sometimes traditional forms "fit" the poem. I refer to my more

conversational dialogue poems as "talking sonnets" where the sonnet form helps shape the conversations. However, for other poems

the form is more organic and evocative of imagism and variable feet. Finally, in the world we live in its hard not to be angered

by war, moved by love and nature, and contemplative about how it all fits together.

I'm also finishing a manuscript for Cy Gist press out of Brooklyn, titled Looking for Lake Texcoco. It's a theme variation on a

painting by Juan O'Gorman, an Irish-Mexican painter at mid (20th) Century. He has a famous painting where an indigenous Mexican

is juxtaposing a map of Mexico City when it was a small island nation with images of the 20 million person or more city it has

become today. The poems are all reflections on Mexico or the United States and Mexico in some way. The poet Guillermo Parra is

translating the poems into Spanish and the book will be a bilingual one.

Slowly, slowly I chip away at translations of Lorca's love sonnets. Yes, perhaps the world's best surrealist poet wrote sonnets!

He wrote them to his lover(s). Most of the world didn't know about them until 1985. His estate was ashamed that the poems

revealed Lorca's homosexuality and suppressed them. It wasn't until other (wrong) versions began to circulate and outside

pressure until the family released them. There are only twelve of these poems. I pull these out just a few times a year.

At this point I'd say I've nailed perhaps three but have versions of each.

Where do you find inspiration for writing and what is the strangest thing you've done to find writing material?

This probably sounds corny but I don't search for writing material or look for inspiration. I live my life. Trying to do so and

hitting it sometimes and missing hard sometimes or just being on par most of the time are all the stuff of art and poetry. So, a

poem can be about love, about a teenager at a mall, about my neighbors, about war, about an ancient Chinese edifice as an island

in the 21st Century. I guess the strangest thing I've written in Isolate Flecks is "Drive bye." It's a poem where I personify a

dead child in a grave telling the story how she was killed.

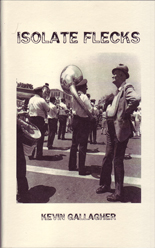

Talk about your chapbook, Isolate Flecks (Cervena Barva Press, 2008).

The title, Isolate Flecks, comes from a William Carlos Williams poem titled "To Elsie." The full line is "It is only in isolate flecks

that something is given off." These poems were written sporadically over the period 1990 to 2006 so in many ways they are "isolated" incidents.

But together they hopefully give something off. There are humorous poems in there about Freddy Sapienza, poems about places like Gloucester

and China, love poems, basically all sorts of things I've run into or that have run into me over the years.

Talk about Compost. How long was it in existence? What type of work did you look for?

Why did it cease publication? Recently, you published an anthology called Compost: 12 Years of art, literature & ideas.

Talk about this anthology. By the way, it is an excellent anthology.

Many of the writers in it influence me.

Here's an adaptation of the intro I co-wrote with Margaret Bezucha to the anthology. I think it sums it up:

"Twelve years ago, a guy named Bush was president, the country was in the midst of turmoil in the Middle East, and, although

the president enjoyed unprecedented support, the seeds of opposition were beginning to spread -especially overseas. Some things

never change, but others do and did."

Those of us who came to found compost, a handful of young poets and artists then living in Jamaica Plain (one of Boston's southern neighborhoods),

saw ourselves as part of that seemingly growing cast of those seeking a different world. How could the Berlin Wall have just fallen,

Mandela have just become victorious in South Africa, Pinochet have left office, and Europe have just united into a common market,

all peacefully, while the United States pursued war overseas, and seemed bliss at home?

Meanwhile, Boston was experiencing a harsh recession and Jamaica Plain (JP) became the low rent mecca for many aspiring artists,

musicians and writers. Many of these folks ended (or started!) their days at Brendan Behan Pub, which, in hindsight had much

more in common with its namesake than its name alone. This group of emerging artists saw the Boston (and national) area poetry

scene as at a lull. To us, the long standing clan of university-based magazines seemed to have an iron curtain that blocked

out innovation and all of our submissions. It was at that time when we learned of Gloria's BLUR (Boston Literary Review),

which was one of the only other independent mags around. Indeed, one of her books was published in a small tin box that

inspired us to think out of the box for the format of our magazine.

Eventually, a blend of inspiration, naivety, technology, desperation, and indeed some vision led a small group of us to

found compost magazine. compost, according to good dictionaries, means

"a. a composition, combination, compound.

b. a literary composition, a compendium." Our stated mission was to help facilitate a better understanding of the world's people

through art and literature. Although we did not articulate it as such in the beginning, looking back, our

editorial position had four planks:

- Re-place poetry in its proper artistic context: alongside visual art, theater, and discussions of society at large;

- Attempt to re-internationalize poetry in the United States;

- Showcase Boston area artists alongside emerging and established artists across the U.S. and the globe;

- Expand the traditional audience for poetry to include the community of the artists themselves and the general public.

With our Macintosh in hand, we set out to open up the concept of poetry by printing it on a large and wide open page, by

juxtaposing it with artwork, and by publishing it alongside essays, interviews, and plays. Indeed, our first three issues

were printed on 11x17 inch brown kraft paper. Moreover, we sewed each binding with the sewing machine plugged into the same

socket as the Macintosh. Beginning with our fourth issue we solidified our editorial format. Issues four through twelve were

loosely divided into three sections. Each issue had a feature section on the poetry of a culture other than mass culture USA,

a section called "Hear America Singing" which featured established and emerging writers from the U.S., and a section that

presented Boston-area artists and writers.

Much of the inspiration for our international slant on poetry came from James Laughlin and Kenneth Rexroth. Laughlin because his

New Directions introduced generations of readers in the U.S. to world literatures, and Rexroth because did the actual translation

of many of those literatures. Over the years, we have paid homage to each of these extraordinary individuals.

In many ways compost has fallen victim to its success. Compost was always considered a "hobby" or an outlet that would not

interfere with our own art and professions. We put out an issue per year that's it. Initially, this was manageable through

Monday night meetings at an apartment to go over submissions and layout the magazine. Soon things changed. The magazine gained

national recognition and distribution, reaching every Barnes and Noble and Borders in the country. With this came reams of

submissions, and the pressure to grow. In fact, we were almost denied a grant on grounds that we weren't willing to

"take it to the next level." The next level was to hire outreach consultants, put out six issues per year, raise funds

for full time staff members, and put together a working board of directors. We always wanted the magazine to be home grown,

so we resisted such pressure. In the end, the magazine became too much as we wanted to give attention to our individual, to

our families, and to our professions."

Who are you reading now?

Right now, I'm completely immersed in the collected works of Denise Levertov, for reasons I mentioned earlier.

Also, the correspondence between Levertov and Robert Duncan from University of California Press is the second best

correspondence of contemporary letters published in English. Second, in my opinion, to the correspondence between

Pound and Williams. I also want to get a copy of Simic's new book, That Little Something.

He's among the best writers today.

What writers make you tick? Ones that you read over and over

I read William Carlos Williams and Kenneth Rexroth over and over. A month doesn't go by where I haven't read their work.

WCW's music and Rexroth's eye and heart are about the best we have to offer in our language, in my opinion.

Rexroth's love poems (collected as "Sacramental Acts") may be the best love poems we have. I did a tribute for

Jacket to Rexroth a few years back. He's also one of the most misunderstood poets we have.

Rexroth's poetry was not well understood during his lifetime. Born in 1905 in South Bend, Indiana, he moved to

California in the late 1920s and remained there for the rest of his life. It was in California where he emceed

the famous "Six Flags" reading that earned him the name, "the father of the Beats." Rexroth hated such a tag and

was known for replying "an entomologist is not a bug!"

Contrary to the popular label thrust on him, Kenneth Rexroth was a late modern poet, one of the early post-modern poets,

and toward the end of his life (which ended in 1982) became an eastern classicist. Regardless of the form his poetry took,

it always involved at least one of three themes: love, the natural world, or politics.

Early in Rexroth's career, Louis Zukofsky included him in both the special Objectivist issue of Poetry, and in the

famous Objectivist Anthology (though Rexroth considered himself a cubist rather than an objectivist).

Although publication in these venues, as well in popular journals such as Blues, had earned him quite a reputation,

Rexroth soon abandoned cubism for a method that Rexroth scholars call "natural numbers"-poetry that is similar in

syntax and diction to actual speech between humans. This method is exhibited in one of his great love poems,

"As We With Sappho," originally published in his 1944 book, The Phoenix and the Tortoise. In the poem he and his

lover are reading the Greek poet with pauses for the making of love:

Kiss me with your mouth

Wet and ragged, your mouth that tastes

Of my own flesh. Read to me again

The twisting music of that language

That is of all others, itself a work of art.

Many see Rexroth as an erotic mystic who saw our human relationships of love, as well as our life with the natural world,

as equally sacramental. Known to have spent long spells in the Sierra Nevadas, Rexroth wrote many poems expressing the

holiness of the natural world, as in the poem "Hapax,"

The night is full

Of flowers and perfume and honey.

I can see the bees in the moonlight

Flying into the hole under the window,

Glowing faintly like the flying universes.

What does it mean. This is not a question, but

an exclamation.

Either through his own poetry or his relentless campaigns on behalf of younger poets, Rexroth influenced a wide array of

our best living poets. Among them are Jerome Rothenberg, Robert Haas, Carolyn Forche, Philip Levine, and Gary Snyder.

However, Rexroth was also known to be quite cantankerous and at times pretentious. By the time of his death he had alienated

many whom had seen him as a mentor. That part of him has left us and the work remains. In recent months Rexroth tribute

readings have occurred across the country that have included many of his former foes.

In his last years, the line between his translation and his own poetry had blurred. One of his last books was

The Love Poems of Marichiko. Marichiko, he wrote, "is the pen name of a contemporary young woman who lives near

the temple of Marishi-be in Kyoto." The poems became highly regarded in both Japan and the United States for

their simple clarity and emotion:

Fires

Burn in my heart.

No smoke rises.

No one knows.

However, when he learned that he was up for a translation prize for these poems he admitted that he had written them himself.

Kenneth Rexroth started his career a cubist and ended it as a women poet from Japan!

I think I'm about to put Levertov up as the last of my "big three." In fact, the Penguin Modern Poets #9 has become my

favorite book. It's a small paperback that features Williams, Rexroth, and Levertov. You can sneak it hiking, into a

meeting, on a bus, just about anywhere.

I've also loved the work of my former teacher Alan Dugan. He blended an echo of the great Latin poets with an ability

to communicate with anyone. Bob Dylan, William Blake, Frank O'Hara, late Pound, Octavio Paz, Garcia Lorca, all get at

least a look each year. I became totally immersed in the work of Charles Olson while living in Gloucester. Of the living

I love Sherman Alexie, Charles Simic, Pura Lopez Colome, Rosanna Warren and Forrest Gander. Although my poems are quite

different, I always derive inspiration from my longtime friend Anastasios Kozaitis.

You currently teach in the Department of International Relations at Boston University. Talk about your job. You travel

as part of this job mostly to Mexico and Latin America. Please talk about it. How do you find time to write?

I've always been struck by how humans interact with each other and with nature. The deepest way we do this is actually through

the economy where we take things from nature, transform them into things we use, trade and use them, then deposit them back

into the earth as waste. Seems crude but its all there in the second law of thermodynamics and it just about sums it all up,

materially anyway. The challenge for us as a civilization is to make that process a more equitable one for the present

generation without jeopardizing the lives of future generations.

From this vantage point I study the politics, economics, and institutions surrounding globalization, economic development,

and the environment. I focus most on the US and our relationship with Mexico and Latin America because they are our neighbors,

and because we are more integrated with our own hemisphere than anywhere else. I do a lot of on the ground empirical work in

Mexico and spend a lot of time there. It is a great country, like our own. Wonderful and complex history, people, poetry,

and food! I've written a lot about how integration between the US and Mexican economies hasn't been done as efficiently as

in Europe and therefore it hasn't been able to make a dent in Mexico's poor economic and environmental records. Based on

that research I argue that we need a more engaged relationship with our neighbors to the south. Unfortunately we're are

literally building more walls between us and them.

Because this work takes a lot of time and I spend time there its become the subject of my new book. The poet

Anastasios Kozaitis once remarked that he liked my poems but wanted to see more of the "other part" of me in them.

Looking for Lake Texcoco are the poems written in Mexican hotels on "business trips" if you'd call them that.

|