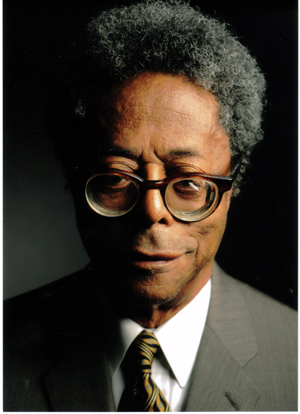

INTERVIEW WITH SAM CORNISH

Truth in Poetry: Interview of Boston Poet Laureate Sam Cornish

by Mignon Ariel King

On a wind-chilled but sunny day in Copley Square, Boston, the Poet Laureate Sam Cornish sits in his office with his coat on.

I am not late, nor are we going outside, yet he looks ready to go someplace important. Mr. Cornish is in some ways the definitive

quirky artist, a native of Baltimore who was influenced by but never quite fit into the Beat Generation or the Black Arts Movement,

race and class preventing a complete sense that either might be his community, a place to settle in.

The Laureate, however, is not truly flighty; he is focused, practical, communicative, self-aware, and his refreshingly old-fashioned

qualities ground him in the present even while making him seem from a bygone era. The old-fashioned charm is worn as loosely as his

overcoat--which it turns out he is simply carrying on his shoulders for later. We do not discuss either the highly-recommended

"Generations" (1971, Beacon Press) or his newest collection "An Apron Full of Beans" (2008, Cavan Kerry). This is a man of

dialogue and observation, not self-promotion.

KING: How long have you been writing poetry, and what got you started?

MR. C: Oh, thirty to forty years. Reading literature and writing in general came first, then poetry. I read the Moderns and the

Black Arts Movement poets, Eliot, Barack, [Langston] Hughes....

KING: Were there other writer heroes in your early years? Who are your heroes now?

MR. C: {He smiles, seems surprised at the question:} Ah. I was into Kerouac, Cummings, Margaret Walker, Gwendolyn Brooks.

Now I like Mary Oliver, Dickinson, of course, a lot of locals, like the Ibbetson Poets. I think Lisa Beatman's very good.

And Glo Mindock, Elizabeth Quinlan. {He adds me to the list here, and we digress for a brief conversation about how he thinks

I am like a Harlem Renaissance writer and Beat writer rolled into one but also part of the "New Age" of Boston poetry, a

multicultural age. I suddenly feel as if he's read my diary. Including and knowing artists are his missions.}

The big boys of Boston--Bidart, Pinsky, those cats--as accomplished as they might be...well, they don't seem to be part of the world

we live in. Small press poets seem to be 'real'. I've got a thing for local multicultural poetry [and international poetry].

It's necessary [for poetry to thrive]. It's got to be gay/straight, men/women, poor too...a lack of pretention--none of that

poems-in-the-garden stuff or, what I'm really tired of, the middle class supposedly suffering without time to write. Oh, boo hoo.

It doesn't embrace poor people's suffering. [That's why I appreciate] the small press, and poets like Doug Holder and Harris Gardner.

I don't know anybody else like that! You walk through your kitchen and there are 10 e-mails on your computer from those two

[about upcoming poetry events and other literary news]. Activism.

KING: Do you identify as a Black or African-American poet? And what does that really mean in 21st-Century America, especially

considering the protest tradition? {I earn another gold star of a smile for this one. He shakes his head in approval.}

MR. C: It depends. It all depends--on what perspective I'm writing from. Like many African-American writers, I have a dual heritage,

at least. European, African, American...I'm all over the place. You know. I like "Free to be you and me." Unfortunately, well,

maybe just circumstantially, the European influence is most powerful. [Partly because of] how some

writers dealt with it. Let's just say Ralph Ellison WAS Black versus "wearing Black." [And]

I'm tired of fabricated nastiness nowadays, people thinking it goes along with their poetic images. They come to your house

as fellow writers, then steal your books, or they leave you with a big bar tab. I'm talking about men here, entertainers too.

Spoken worders. Hip hop!

KING: I'm glad you mentioned that. How do you think Black written-word poets can remain relevant in a

spoken-word generation? Why is this important?

MR. C: Black male poets should be socially-minded as well as literary. These hip-hoppers, with them it's one word after

another, the [spoken-word] poets do it too. It is rhythmic, attracts attention, an audience. It's an audience that moves

but doesn't want to think. I'm slow moving, but have a quick ear. {I look up, and he smiles, just seeing if I was

listening.} It's word-driven, but the content! It's important because there should be some family history and social

responsibility. There's a lack of historical and social depth. [Add those elements] and you could bring that energy

into the classroom and bars [where they have poetry slams]. Young people can relate to truth and honesty in poetry and

come to it, especially problem kids. It's nice for them to have someone write a poem about something they can relate to.

Problems. Overcoming. Dennis Lehane comes to mind.

KING: Do you think the divide between Black men writers and Black women writers has really narrowed significantly since,

say, the Harlem Renaissance or the '60s Black Renaissance? If not, what strategies might close the gap?

MR. C: Whew! It's probably wider. Men complain they can't publish while Black women get published all the time. {I laugh.}

Well, a bit more, but for good reason [having nothing to do with racism]. There's a thing called human sexuality, then there's

just nasty. Some Black male poets write great stuff, then they have to add...let's just say it is a little nasty and shows no

respect for women. {We concur that we don't want to read that either.}

They could have a wider audience. {He sounds more wistful than scolding here.}

KING: Why are you the poet laureate of Boston, specifically? What's so thrilling to you about this city,

personally and professionally?

MR. C: As a kid, I had too much hair, bad feet, patches, liked to read. In Baltimore that meant "gay [lots of homophobia then],

dirty, strange...." Bad enough in general, but in the Black community--I know you know!--I got, "What's wrong with that boy?!"

In Boston I found a home, a community instead of just a few individual poets here and there. The Carpenter Poets do it for fun

and have a sense of community, and Harris [Gardner]!!

Poetry Marathon? Who else has a poetry marathon? In the Cambridge area too. The poets are very supportive, more

open and accessible [than Boston's academic poets.] I get to feel like a person. [They accept change too.] Change

is for the better [in the arts].

In many ways, the poet laureate position is the best thing that ever happened to me--outside of discovering whiskey and music.

{He pauses, pleased with himself as I am cracking up.} Before that, I'd stay away from writers, groups of writers.

I thought they were all pretentious.

KING: Last question. Do you believe in or have a muse?

MR. C: [Laughs.] No! [Thinks a moment.] Kinda yes, kinda no. I believe in God and notebooks. I mean, I carry my

notebooks in case something comes from someplace unexpected, suddenly. I guess something's out there. I'll have to

change my answer to 'yes'--but not in a conventional sense.

He holds doors as we leave the cafe of the Boston Public Library and pauses to appreciate and snap a photo of the lovely

courtyard garden as if he didn't see it regularly. The most fascinating aspect of interviewing Sam Cornish is that he was

interviewing me back the entire time, subtly, just getting to know me. He is very obviously interested in people, especially

those who make up his adoptive city, so much so that he weaves them into the historic and literary traditions of Boston in a

manner that is simultaneously warm and analytical. Sam Cornish is the first poet laureate of Boston, Massachusetts.

Our city has a reason to be very proud of its important new directions.

|