|

May 11, 2009

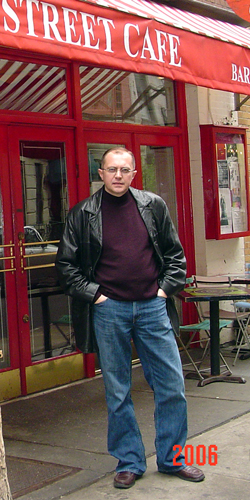

Vasyl Makhno is a Ukrainian poet, essayist, translator and playwright. He is the author of seven collections of poetry:

Skhyma, Caesar's Solitude, The Book of Hills and Hours, The Flipper of the Fish, 38 Poems about New York and Some Other Things,

Cornelia Street Café; a book of essays, The Gertrude Stein Memorial Cultural and Recreation Park; and two plays,

Coney Island and Bitch/Beach Generation. His work has been translated into Polish, English, German, Serbian, Romanian,

Slovene, Russian, Lithuanian, Malayalam, Czech, and Belarusian. He has been living in New York since 2000. Makhno was

interviewed by Alexander J. Motyl, a professor at Rutgers University and the author of several novels.

You began your poetic career in Ukraine. How has separation from your native language affected your poetry?

I exchanged my native country for America eight years ago. The contrast between the two cultures and languages gave me a taste of

something I hadn't experienced before. It made my poetry more expansive. The city provided me with new themes and gave my poetry a

new aesthetic impulse. In 38 Poems about New York and Some Other Things, I focus on New York's streets and sounds, and the poets

who've lived here. Something similar happened to me when I lived in Krakow, but it was nothing compared to the American experience,

which has been unique and absolutely remarkable.

What's so unique and remarkable about that experience?

Krakow is Europe, after all, but America, and especially New York, is a madness that never leaves you. In contrast to Europe,

America doesn't insist that you be American. No one cares if you reject its collective psyche or way of life; no one reminds you

of your otherness or foreignness. New York doesn't comprehend your loneliness; the city just makes a joke of it, leading you by

the hand through its fantastic labyrinths, exposing you to countless distractions, showing you various ethnic groups, cultures,

and national cuisines. The city offers you an alternative-and it's always open to dialogue. Of course, you may not be ready for

such a dialogue and you may not want to accept its invitation to wander its labyrinths.

How did your fascination with New York's Beat poets come about?

In Ukraine, I wasn't very aware of the Beat generation. After all, during my youth our knowledge of American literature ended with

Hemingway. When I arrived in New York, I absorbed this exotic poetry. It was incredible to walk the same streets and sit in the same

cafes as the Beats and the poets of the New York School. I began to read their writings and eventually I even met John Ashbery.

This meeting was probably of no significance to him, but to me it was earth-shattering.

Has American poetry influenced you?

Yes and no. That ambiguity is reflective of my East European approach to poets as discoverers of the strange. I've always been

fascinated by those things in American poetry that are absent, or almost absent, in Ukrainian or Slavic poetry-such as continually

changing poetic strategies, rationalism, openness to and creation of everyday language, less abstract images and symbols, and

attempts to expand the possibilities of language and poetry. But American poetry is also experiencing a crisis. The entire world

has adopted the New York School's strategy of banality and considers that everything can be poetry, from New York garbage to Fifth

Avenue ads. Every step forward entails some debasement, which is fine, since realizing this enables you to seek out new forms and

language.

Which American poets have influenced you the most?

Any Slavic poet can name a few English-language poets such as Eliot, Ashbery, Pound, or Platt and thereby stake a claim in this

tradition, but truly engaging them can only be done in English and not in translation. One Russian critic claims to see Anglo-American

influences in my poetry, but I'm not so sure. And besides, while it's true that Ashbery has influenced me, what does that really

mean in light of the fact that many critics consider him to be the best exemplar of European traditions in American poetry? That

said, I especially like Allen Ginsburg and the Beats, the New York School, Derek Wolcott, and Charles Simic.

Do you still consider yourself a Ukrainian poet?

Of course. My roots go back to Ukraine and I am and always will be a Ukrainian at heart. But I also consider myself European and a

New Yorker. It's funny, but I'm already considered an American writer in Ukraine. I agree with Salman Rushdie that a global society of

displaced writers currently create literature out of wedlock. Regardless of where they're from, these writers share a new literary

language, are marked by conflicts between their countries of origin and their countries of settlement, and are shaped by borderland

cultures and psyches.

But yours was a very specific generation. Surely that makes you different.

My generation, like so many others, experienced cataclysms and disappointments and was not, in that sense, unique. On the other hand,

I belong to a generation that, at the age of 15, pined for American jeans, which cost both your parents' monthly wage on the

black market. We listened clandestinely to foreign radio stations, went crazy over Western music, and read Solzhenitsyn's One Day

in the Life of Ivan Denisovich under the covers. Then we experienced the war in Afghanistan and the Soviet collapse. We were a

transitional generation at a transitional time. We produced criminals, Mafiosi, nationalists, communists, gays, feminists, writers,

and emigrants-heroes and antiheroes of various kinds.

Who belongs to and creates Ukrainian culture?

Obviously, Ukrainian culture is created in Ukraine. But Ukrainian culture also exists wherever Ukrainian artists have found refuge-as

in Paris during the 1920s and 1930s or in America after World War II. Consider Samuel Beckett-an Irishman who wrote in French and

English. Does he belong to Irish, English, or French culture-or to all three? I do think that someone living in Ukraine and writing

in Russian may contribute to Ukrainian culture. Can a writer living outside Ukraine be Ukrainian while writing in English, Russian,

or Chinese? I'm not sure that even an excellent writer like Askold Melnyczuk is contributing to Ukrainian culture while writing in

English.

So English-language translations of your poetry don't belong to Ukrainian culture?

Not quite. My poems were originally written in Ukrainian; translations can't change my specifically Ukrainian mentality.

How did the New York Group of Ukrainian writers contribute to Ukrainian culture?

People may not appreciate it here or in Ukraine, but Ukrainian literature would be much poorer without them. Yuriy Tarnawsky's

"poetry of anti-poetry" has, as Bohdan Rubchak once said, affected our poetry like a virus, undermining sentimentality and

pseudo-profundity. A woman poet from Ukraine once told me that it was only after reading some of Rubchak's poems that she

finally understood what economy of expression means. To which I'd add that his cultural allusions intertwine the world with

Ukraine. Bohdan Boychuk explores history, eroticism, and human existence while moving between Western rationalism and national

idealism. Wira Wowk, Patricia Kylyna, Emma Andijewska, Zhenya Vasylkivs'ka, and Maria Rewakowicz have exploded form as well as

linguistic and conceptual taboos. But it's important to realize that the New York Group's innovations were also rooted in Ukrainian

literary traditions. People continue to respond to their work both positively and negatively, because they're still provoking and

affecting readers.

But contemporary Ukrainian literature is, as you say, being crafted in Ukraine. What's your assessment of current trends?

I take it as axiomatic that Ukrainian literature will never be like English, American, German, or French literature. Ukrainian

literature is interesting as what it is-as a literature in motion, reflecting the changes that befell the Soviet Union before and

after it collapsed. Ukrainian literature did evolve in the twentieth century, of course, but it was only after Ukraine became

independent that our literature received carte-blanche to be free, to escape censorship, and to experience the clash of generations.

Similar processes also took place in Poland, Romania, Hungary, and the Baltic states. But as Soviet readers, who always hungered

for good books, were replaced by apathetic, impoverished, and confused readers, Ukrainian writers came face to face with a dilemma:

either to produce for the market in Ukrainian, while abandoning literary standards, or to abandon readers to Russian-language authors.

The struggle continues, but now both writers and readers have made concessions and reached a modus vivendi. As a result,

Ukrainian texts get translated into European languages, Ukrainian authors take part in international festivals, and Ukrainian

literature is actually considered European by the Poles and Germans.

How do you write poetry?

I used to write my poems with a pen. Today I usually type them on my laptop. And that's the first important change. As to the

actual process, I don't write when half-awake or drunk. For me writing is a fully conscious activity provoked by the desire to

verbalize intellectual or emotional states. I usually write a poem as a whole, and then make changes. Sometimes love of a text

turns to hatred and a desire to destroy it-which I interpret as a kind of Oedipal complex, a constant struggle with oneself and

against oneself.

Where do you get your ideas for poems?

From many different things-a New York street or a Starbucks cafe, a book, my childhood, my memories. My poem,

"Would You Stop Loving Her if You Knew She Was a Lesbian?", was an ad in the subway. I also get ideas from my travels.

Most of the essays in The Gertrude Stein Memorial Cultural and Recreation Park are exploratory wanderings based on real

countries and cultures. My visit to India "led": to my Indian poems, while Berlin served to inspire the cycle I'm currently

writing. Obviously, New York has been my major source of inspiration. I didn't adapt it to me; I tried to concretize my own

visions and psychological states. Themes, like life, are always changing; one's voice has to remain authentic and clear.

Who is your audience?

My ideal readers have no age, but they probably have a philosophical bent.

Have you ever written novels?

I've written essays, but sometimes I think I'd like to write a novel about my generation as it moved from the collapse of the

Soviet Union to middle age.

Are you related to Nestor Makhno?

Alas, no. My father comes from a village called Dubno, which is now in Poland. The two most common names in Dubno were Hohol

and Makhno. I think that my ancestors came there from eastern Ukraine. It's quite possible that Nestor and I were relatives

in the 1700s.

Vasyl Makhno, thank you.

|