|

July, 2005

Aug. 2005

Sept. 2005

Oct. 2005

Nov. 2005

Dec. 2005

Jan. 2006

Feb. 2006

Mar. 2006

Apr. 2006

May 2006

June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

ČERVENÁ BARVA PRESS NEWSLETTER

Gloria Mindock, Editor Issue No. 39 October, 2008

INDEX

Welcome to the October, 2008 Newsletter.

October is fund-raising month! Help out by making a donation or buying a book. We depend on this for publishing all our

books and publicity. If we don't have the funds, production slows down.

Donate on the website at the Fundraising Page

| |

<<< Use this button to donate online! |

This month, Červená Barva Press has two readings.

October 15, 2008

7:00 PM, Free

Pierre Menard Gallery

10 Arrow St.

Cambridge, MA

Reception to follow

Readers: John Amen, Kevin Gallagher and Glenn Sheldon

October 30th 7:00 PM, Free

KGB Bar

85 E. 4th Street,

New York, NY

Hosted by Gloria Mindock editor, Červená Barva Press

Readers: Andrey Gritsman, Eric Darton, Roberta Swann, Roger Sedarat

Special Guest Reader: Denis Emorine, who will be here from France

This month, Glenn Sheldon and I will be reading at the Brockton Public Library.

Brockton Public Library

304 Main St., Brockton, MA

October 18th 3:30 PM

Workshop and open reading from 12:00-3:15 PM

Hosted by Frank Miller

Interviewed this month: Djelloul Marbrook, Askold Melnyczuk, Eric Wasserman

It has been one year this month since my book, Blood Soaked Dresses, was published by Ibbetson St. Press.

What a wonderful time it has been! So many people have bought the book and it is still selling well according to

Ibbetson St. Press. Thank you Doug Holder for everything you have done and to everyone

involved with the book in anyway who helped make it possible especially the El Salvadoran Refugees.

In the Raves section of this newsletter, you will see a new anthology listed called, Stranger At Home, An Anthology,

American Poetry With An Accent by various poets. This is the best anthology I've ever read. What a rarity and a gift

this book is. Please buy it. I highly recommend it!

Stranger At Home, An Anthology, American Poetry With An Accent by Interpoezia

www.interpoezia.net

Published by Numina Press, 2008

172 pages

ISBN: 978-0-9753615-3-5

www.numinapress.com

Price: $15.95

Edited By: Andrey Gritsman, Roger Weingarten, Kurt Brown and Carmen Firan

Contributors: Laure-Anne Bosselaar, Ilya Bernstein, Nina Cassian, Srinjay Chakravarti, Yu-Han Chao, Alex Cigale,

Andrei Codrescu, Denis Emorine, Carmen Firan, Eric Gamalinda, Edvige Giunta, Rafael Jesus Gonzalez, Rigoberto Gonzalez,

Yanina Gotsulsky, Aniela Gregorek, Jerzy Gregorek, Andrey Gritsman, Andrei Guruianu, Gabor G. Gyukics, Anselm Hollo,

Julia Istomina, Ilya Kaminsky, Tsipi Keller, Danuta E. Kosk-Kosicka, Dean Kostos, Yahia Samir Lababidi, Shahe Mankerian,

Irina Mashinski, Sawako Nakayasu, Eugen Ostashevsky, Christina Perissinotto, Wang Ping, Adrian Sangeorzan, Mario Susko,

Goran Tomcic, Davide Trame, Alexei Tsvetkov, Chris Tysh, Helen Tzagoloff, Florencia Vareta, Jumoke Verissimo,

Shanxing Wang, Matvei Yankelevich

City of the Sun, Poems by Stanley Nelson

Presa :s: Press, 2008

126 pages

ISBN: 978-0-9800081-2-8

To order: www.presapress.com

$15.95

"…Nelson's epic is concerned with a desperately eternal theme: the search for meaning and beauty that has led centuries

of men and women to push physical, mental and spiritual boundaries to exhaustion."

--The Pedestal

Červená Barva Press will review books and CD's within the next few months by Gisela Falabela, Larissa Shmailo,

Djelloul Marbrook, and Pamela Laskin. More will follow in the later months.

The press is swamped so we will get them out as soon as we can.

Come Join the Poets!

All Events Are Free and Open to the Public

More than 20 Poets from China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and elsewhere

THE SIMMONS INTERNATIONAL CHINESE POETRY FESTIVAL

OCTOBER 4-5, 2008

SIMMONS COLLEGE

ZORA NEALE HURSTON LITERARY CENTER

300 THE FENWAY

BOSTON, MA 02115

Afaa M. Weaver

Chairman |

Dr. Michelle Yeh

Co-Chairman |

Eleanor Goodman

Assistant |

POETS AS DIPLOMATS? RARE INTERNATIONAL GATHERING OF CHINESE POETS OCT. 4-5 AT SIMMONS COLLEGE

Chinese, American Poets to use Poetic Translation

as a Model for Diplomacy

BOSTON (August 22, 2008) -- In what may be one of the most unusual ways to help improve communication and relations between

modern day China and America, leading Chinese poets will travel to Simmons College in Boston Oct. 4-5 for an International

Chinese Poetry Festival, using poetic translation as a model for diplomacy during today's challenging times.

More than two dozen well-known poets from China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and the United States as well as academic scholars and translators,

will meet to explore ways to improve communications between the cultures through the exchange and translation of poetry. The festival,

which is free and open to the public, will feature discussions about the difficulty of accurately translating poems between two radically

different cultures, readings of modern and traditional Chinese poetry in English and Chinese, and an explorations of the significance of

Chinese poetry in world literature.

The gathering will also focus on women and their role in contemporary Chinese poetry.

The two-day festival will be on the Simmons College campus at 300 The Fenway, Boston in the Linda Paresky Conference Center of the

Main College Building. (For more information about the festival schedule, visit www.simmons.edu/znh.

You may also call (617) 521-2175 or email znhlc@simmons.edu.

Among the poets attending are Leung Ping Kwan, Zhou Zan, Hong Hong, Marilyn Chin,

Zang Di, Zhang Er, Yi Sha, Kelly Tsai, Ye Mimi and Shinyu Pai.

The festival is founded by nationally acclaimed poet Afaa Michael Weaver, a Simmons College professor and director of

the Zora Neale Hurston Literary Center at Simmons. Weaver's new book The Plum Flower Dance includes "American Income,"

a poem that was awarded the 2008 Pushcart Prize. Proficient in Mandarin, Weaver was the first African-American poet to

teach American literature in Taiwan. The festival is co-chaired by Dr. Michelle Yeh of the University of California, Davis.

Write a bio about yourself.

I was a few months old when my mother brought me from Algiers to her mother and sister in Brooklyn. I think she had stopped

over in France and England, but I never learned why. My grandmother, Hilda, said I looked like a plucked chicken. Her doctor

told her I probably wouldn't survive. But Grandma was determined I wasn't going to die on her watch, so she strained soups and

spoon-fed me. She took me to Coney Island every day to take in the sea air, and I slowly got well. When I was five my mother,

seeing that I regarded Grandma and my Aunt Dorothy as my mothers, sent me to a

Christian Scientist boarding school on Long Island.

There was trouble from the start. I arrived in America under a cloud of myth. My mother claimed my father had died of a hunting

accident while she was pregnant. It wasn't until 1992 that I found out he had lived until 1978. It turns out that although he

had had an affair with my mother, he chose to remain with a Scottish woman with whom he had been living. After the Scot's death

he had three children with a woman who is still alive in Algeria. I have corresponded with this family.

I got a superb English education at the boarding school until I was 15, because English people had founded the school and

many of the students were wartime evacuees from England. But I suffered sexual molestation of various kinds and brutality

from bullies. I also learned how to take care of myself and to confront bullies.

I then lived for three years with my mother and stepfather in Manhattan, attended a marvelous prep school and continued to

excel academically, but I had never seen drinking or smoking before, and the household was violent and upsetting.

The presence of alcohol proved to be dangerous. I quickly became a secret alcoholic. In college, at Columbia, I did well for

two years but began missing classes and neglecting studies. I didn't know it, but I was looking into the abyss, a first-class

psychotic break. The day before my 18th birthday in August my mother kicked me out. We had never gotten along very well. My

stepfather was now elderly and ill. In a few more months, living alone, I broke down. One day everything just got too big,

too loud, too close, and I put my books down on a bench, got on a subway train and never returned to college. It never occurred

to me that I had what then would have been called a nervous breakdown.

I served in the Navy on active duty for five years and then reserve duty and started a newspaper career in

Rhode Island at The Providence Journal.

I wrote poems from age 14 into my late 30s, but at some point I recognized that I didn't want to be caught

dead saying what I meant or meaning what I said. So I stopped writing poems, but I kept on reading poetry and

studying poetics. In 1971 a doctor told me I was about to die of alcoholism. Then followed a long struggle to

stay sober and deal with the underlying depression that I had used alcohol to medicate. Once I had been sober for

a few years, it dawned on me that I was an adolescent. I've been spending my life since then trying to grow up.

I started writing fiction in 1989, thinking it might be my real calling. But something about the terrorist attacks of

September 11th, 2001, awakened me to my own poetic impulse, and I started walking around Manhattan writing poems.

People would look at me and smile, and I'd smile back, and after a while I said to myself, This is my city, my hometown,

and I love it, no matter what happened to me here, no matter how savage the memories I have to relive, I love this city

and I'm going to say so. I'm going to take it back from the family that found me so inconvenient. I didn't know it then,

but many of the poems would be about being inconvenient to others, about feeling less than welcome in situations where

people were patting themselves on the back for welcoming you, about always being invited to treat your own intuition with

contempt, and being punished if you didn't accept the invitation.

Describe the room you write in.

My usual practice is to walk around Manhattan or upstate towns and country roads, scribbling the makings of a poem

into notebooks. So my room is usually a country road or city streets, sometimes a café. I'm kind of particular about

the notebooks. I favor translucent plastic covers and telescoping ballpoints. But I'll write on napkins and newspapers

if I have to. I sleep with a large notebook and pen, because I often wake up with a poem in mind. When I'm in our

apartment in Manhattan I tend to write in our dining area under a large painting by Andrew Franck, a Woodstock

homeopathic doctor, artist, musician and alchemist. Upstate in Germantown I write all over the house, but my

favorite spot is a light-filled front room where one of my mother's paintings hangs. It's called Plateau of the

Green Moon. (I can give you a jpg image of it if you wish.)

At some point I transcribe my notebooks to a laptop-I rarely carry a laptop around-and then most poems go through who

knows how many changes. I never really stop working on a poem. Some come easily. Others daunt me. If something about a

poem is eluding me, I usually call it a draft and keep it on my computer desktop. But I keep the notebooks handy, too,

even when they're filled, because sometimes I see something I want to change or add when I glance at my handwriting.

The handwriting often gives me a clue, an insight that formal typography doesn't. I can relive a recognition by

examining my handwriting. Sometimes my handwriting is quite studied and formal; other times it's hurried and ragged.

That tells me something about my original impetus to write a poem, and I find that important, because I fear perfecting

a poem to the point where it is so studied that it has left behind the original idea.

In 2007, your manuscript won the Tom and Stan Wick Prize for poetry from Kent State University. Your first poetry book,

Far From Algiers, has just been released. Talk about your book.

A few years ago I woke up in the middle of the night-which I often do-feeling overwhelmed by what I had written. I

felt that I needed to reconnect to it. I started to make stacks on the floor of our front room upstate in Germantown.

I ended up with 15 stacks for as many general categories. But the stacks were quite uneven. I noticed that the 11th

stack was by far the tallest, and it seemed to me that these poems were about belonging and unbelonging, about them and

us. I saw that I belonged to them, whereas my mother's family, it seemed to me, belonged to us. I began to see this as

the central crisis in my life. But of course it wasn't that simple. Nothing ever is, our fundamentalist friends

notwithstanding. I saw, for example, that my presence had opened up wounds in my mother's family. If I had looked

like them, the wounds would have been superficial, but I didn't look like them, so I had to be the outsider. Not

that there wasn't immense love and devotion from my grandmother Hilda and my Aunt Dorothy, my mother's younger sister,

but it couldn't protect me from that sense of foreignness, of being the family issue, the problem.

I don't know how the title came to me. There is a title poem, so I suppose I just fell upon it, thinking it would convey

that sense of struggling to belong in a situation where I was perceived as a problem. My mother's family felt she had handled

matters badly, and I was one of the matters. I think in time she came to resent the solution, which had been to park me with

Hilda and Dorothy. Predictably, I came to feel I had two mothers, Grandma Hilda and my young Aunt Dorothy. So, when I was five,

my mother removed me to a boarding school, and I don't think Hilda and Dorothy ever forgave her for that.

At some point I became dimly aware of the nature of my rebirth as a poet. My hometown, New York, had been attacked. I

felt injured and angry, as all New Yorkers did. But I noticed that at the same time we were all coming together there was

also this bitter response, the flag-waving, the underlying message that if you didn't hate somebody, if you didn't want to

bomb anybody the president might select for bombing, then you weren't American and you didn't belong. So while we were

grieving and coming together, some of us were also venting nativist, them-and- us sentiments, which of course are at play

in the elections. This called up my own lifelong struggle with the them-and-us syndrome, and in this case the Arabs were

them. My father of course had been an Arab. I had no doubt about my Americanism, my patriotism. But I could readily see

that what some Americans meant, without saying it out loud, was that if you didn't look North European you were essentially

suspect. And if you didn't look acceptable, then at very least you had to support any response the extreme right might cook

up to deal with the situation so that you could prove yourself to the rest of the country. But who was the rest of the

country? At best, some 25 percent of Americans are white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Certainly not anywhere near a majority.

The U.S. Army, I could see, looks like the whole country, like our demographics, but the governments we're electing do not.

In the news footage from Washington you can see our federal government doesn't look like our army, it doesn't look like the

sons and daughters we are sending to die for us. So I began to see that I had opened a wound, not only in my own soul but

also in the country's. I took a deep breath and put a manuscript together, and it was my great good luck (or was it

synchronicity?) that Toi Derricotte read the manuscript, because she had suffered that very wound and understood it well.

(To order: http://upress.kent.edu/books/Marbrook_D.htm )

Talk about your book, Saraceno. How long did it take to write? You had personal experience with the Mafia to write this book.

How did your life growing up influence this book of fiction?

Saraceno was my very first work of fiction. I started it in February 1989. I was in Woodstock, nursing Bill, my mother's

second husband. My mother, then 85, was unprepared to cope with his illness. He lived in a beautiful little 1880s

Italianate cottage next to a famous old hotel built by his grandfather in 1929. It had last operated in 1964. In

the evenings when he fell asleep I would sit in the lobby of this ghostly unheated building, pecking away on an antique

Oliver, one of the many things Bill had collected over the years. Every once in a while I'd get up and throw a piece of

broken furniture into a huge fireplace.

What emerged was an encounter with a Hell's Kitchen thug named Billy in the early 1950s. At that time I was struggling to

stay in college. My mother had kicked me out, and I had already become alcoholic. I was working in a cigar store on

Eighth Avenue, selling newspapers out front. Billy had just spent seven years in Dannemora. He was extraordinarily

handsome, self-possessed and breathtakingly violent. He had been sentenced to Dannemora for savagely beating a cop.

I liked him, and sitting so many years later in that windy hotel with the fire crackling, I recognized that I wanted

to write about him, to imagine what might have become of him. I had played a role in connecting him to La Famiglia.

The Mafia was a subject I could write about with some authority, at least its cultural aspects, because my stepfather,

Dominick, was a Sicilian and had been a chum of Charlie (Lucky) Luciano. I felt I could say something that hadn't quite

been said before about the Mafia. But mostly I wanted to write a story about friendship and honor in an unlikely place.

Saraceno was printed but never distributed, although new and used copies are trading actively on the web. The small

Canadian publisher failed before distributing the book. But because it was a print-on-demand book published by BookSurge,

Amazon's POD subsidiary, Amazon kept reordering it until I realized it hadn't been distributed or promoted and withdrew

the copyright. So some copies are still out there in the world, and it still gets a surprising amount of attention on the

web. And of course POD books are ignored by the mainstream media, for the most part. The book got some good reviews, and I

had hoped it would open the door to publishing some of my other fiction.

Several months ago a story taken from an unpublished novel won Literal Latté's first prize in fiction.

It will be included in a Literal Latté anthology.

You worked as a reporter for The Providence Journal. How long did you do this?

Did any of the stories you covered fuel your writing?

I had been contributing to The Journal when I was stationed at Quonset Point in the Navy. When I was discharged The Journal

amazingly gave me a chance during one spring and summer to compete with journalism school graduates for a job. I had no degree

at all, although I had studied for three years at Columbia and was something of an autodidact (I still am). I

stayed with The Journal from 1958 to 1964. And yes, I'm sure some of the stories I covered influenced my writing,

but not as much as my experience working as a teenager in Manhattan. I then became an editor at a number of newspapers

and finally an executive editor for small and mid-sized dailies. By the time I managed to stop drinking and start

growing up, journalism had changed and so had I. I was fiercely idealistic, unrealistically so, and as a sober and

reasonably self-aware person I kept butting up against the commercial censorship and distortion of news that is pervasive

in the mainstream media. I wasn't able or willing to make the compromises necessary to go along and therefore get along.

It was a form of immaturity, but also an awareness I hadn't had before. I didn't feel in any way superior to all those

wonderful colleagues who could get along in the business. In fact, I felt inferior, disabled in the way that persons with

learning disabilities are handicapped. And by this time I was past 50. I had no illusions about being successful as a

fiction writer. But I did think I had something to say, which hadn't been the case before. I knew I didn't want to write

thrillers or police procedurals, but I knew my head was teeming with characters who wanted to be heard.

I had no idea what I was up against trying to get published, and to make matters worse, I'm not a networker. I have trouble

enough answering the phone, much less picking it up and trying to interest a stranger in anything I'm doing. I feel about

that sort of thing the way I feel about walking into a gallery in a museum-I'm intruding on the painting and the painter.

I have no business in his or her head. If I look at Primavera I start thinking the hounds of Diana are going to hunt me

down and tear me to pieces. Everybody else's privacy is so sacred to me I can't imagine how I could have presumed to be a

reporter. Maybe that's why I became an editor. I think the way we intrude on each other in the popular press is obscene and

savage. And yet I'm perfectly willing to call the intrusions of Virginia Woolf and D.H. Lawrence art. Well, who said we're

obliged to make sense?

You were editor for many newspapers including The Elmira (NY) Star Gazette, The Baltimore Sun, The Winston-Salem Journal

and Sentinel, The Washington Star, and Media Newspapers in Northeast Ohio and Patterson and Passaic, NJ. What was this

experience like? What were the challenges you faced?

Working for The Journal was halcyon. Working in Elmira was formative and deeply rewarding. I learned how to get a newspaper

out onto the street, how to design one, how to follow production from start to finish. The Baltimore Sun instilled the value

of excellence, taking pains, precision, high literacy. But The Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel gave me the most hospitable

and gracious work environment, the loveliest people, and the most memorable period in my newspaper career. The people in Ohio

were unfailingly friendly and welcoming, but the work there and in New Jersey was exhausting, demanding, and filled with the

challenges of trying to do more with less. The entire industry had changed by the mid-1980s. Newspapers were cutting back

ruthlessly, trying to find new ways to engage readers, and hoping that by stringencies rather than investment they could

turn the industry around. I think we put out very good newspapers, but each day was a tour de force rather than a steady

march of good journalism, and I simply wasn't up to the long haul, whatever that might have turned out to be.

How long were you the English editor for Arabesques Literary and Cultural Review? Recently, their website disappeared.

Do you know what happened? I have had work published in this magazine. I loved their diversity in publishing.

Talk about your experience. Let's hope this journal will be back soon.

It recently reappeared on the web, with a bit of help from my wife Marilyn and me. I am still an advisory editor for the

English version, but I find I don't have the time to actively edit each contribution. Arabesques is a brave venture by a

young Algerian poet in the western city of Chlef. Amari Hamadene has been struggling to find the resources to publish

literature and cultural inquiry in French, Arabic and English. It's an immense task of bridge building between cultures

that are often in conflict. Amari's design sense is superb, and if there were any justice in the world his own government

and the French- and English- speaking worlds would support his endeavor, because the news we get is about oil, terrorism,

sectarian conflict, instability, death-whereas there is good news and good will throughout the world, and Amari's project

is a bright instance of that. What he's trying to do is more important than the latest oil price or terrorist attack, but

the media don't see things that way. He published the title poem of my book, Far From Algiers.

You are a regular contributor to the Istanbul Literary Review. I always look forward to reading and publishing your work.

Talk about the importance of international magazines.

The vogue is to think we are on information overload, but the creative thinking, the recognitions that challenge our

minds and hearten us are conspicuously absent in the mainstream media. On television the Discovery and History channels

are infinitely more edifying than cable news or the networks. In the print medium The New Yorker is far more likely to

enlighten us than newspapers. Editors have been supplanted by marketers who regard culture as a horse race and define

success as winning. Under the circumstances, the small presses and journals like Istanbul Literary Review are essential

to the exchange of ideas and the nurture of creativity. And among these the international journals like ILR and Arabesques

fulfill a special role, because they transcend national boundaries and free artists and thinkers to communicate on a

grander scale. They transcend the fundamentalism that plagues the world in almost every culture. Fundamentalism in essence

is the impulse to control other people's minds, to limit perspective and inquiry, to impose inquisitions and dampen

ecstatic wonder. The international journals stand over and against all this. The tension in the world is not essentially

a response to Western capitalism, as seems to be the popular perception, but rather a conflict between the spirit of

inquiry and the fear-driven compulsion to shut inquiry down and impose dogma. The tension is political only in the sense

that governments respond to one impulse or another. So anyone who is about building bridges between cultures and the free

exchange of ideas stands against putting the human mind in lockdown.

Your mother, Juanita Marbrook Guccione, and her sister, Irene Rice Pereira were famous painters. What was it like growing up

in such an artistic family?

I lived with my mother for only about three and a half years-the first few months of my life in Algiers and England, when I

was deathly ill, and then between the ages of 15 and 18 in Manhattan. Our relationship was troubled but profoundly involved.

After her death I could see quite clearly that I had always been a reminder of something that had gone terribly wrong in her

life, and I was overwhelmed with sorrow about that. I had always felt like an intrusion. Her paintings were her children, and

now they're mine, and it's up to me to see that the world sees them. It was exciting to be around my mother and my Aunt Irene.

My relationship with Irene was serene, untroubled, and deep, because we shared an interest in metaphysics, history, the life of

the mind. Irene was always a quiet refuge for me, and I admired her inordinately as a painter and a person. My mother was a

great beauty, the kind men gape at in the street. This was both useful and problematic for her. Few people ever got past her

looks to know her. Irene was also beautiful, but not in such a conventional way. Nobody made a big play for Irene unless they

thought they could deal with that fierce intellect. I once mentioned that to her. She smiled, turned into the kitchen to make

us tea and said over her shoulder, 'You're perceptive.' My mother was inclined to think men make fools of themselves over women.

She often looked at me as if she didn't have the faintest notion where I came from. I loved this, while at the same time it

chilled me. I thought she really didn't have the faintest notion, and neither did I, since she had mythologized her

relationship with my father and assigned to him a premature death, which was rather like sticking pins in a doll.

Certainly my mother and Irene instilled in me a lifelong love of art. I thought they were gods, no matter what else I

might see in their lives. I thought they weren't subject to the same rules as mortals, and my mother certainly agreed.

Irene, on the other hand, reserved her contempt not for people who disagreed with her but for soap opera. She loathed

melodrama and exhibitionism.

Since you were born in Algiers, when did you move to America? Talk about your immigration experience.

Do you ever go back to Algiers?

It wasn't an immigration experience in the usual sense. I was an infant when I arrived in Brooklyn at Grandma's home. I don't

know where my mother took me when she left Algiers. I was a few weeks or months old. I don't know the exact time line. So I

have no memory at all of Algeria, which is probably a blessing, since I was born to a troubled trio, my young father, my mother,

age 30, and my father's rich companion, who was in her forties. Maybe surviving didn't seem like an

option to me.

I remember my first five years in Brooklyn with a good bit of clarity. Grandma hired a wonderful nanny, Peggy, whom I

worshipped, and between Peggy and her family and Grandma and Dorothy I was very happy until the day my mother pulled me

out and sent me to boarding school. Dorothy was athletic and used to roller skate and ice skate with me on her shoulders,

and I have fond memories of sitting on her shoulders and Peggy's too, braiding their hair. From Grandma, Dorothy and Peggy

I acquired the notion that nothing untoward in my life would ever come from women. But boarding school was to shockingly

disabuse me of that notion.

Is your wife Marilyn a writer?

She should be. She would be a wonderful writer. But she has chosen to be an editor. She edited and published reports

for the Justice Department in Washington for many years, and dozens of their documents and books bear her name. Now she

is my editor, and without her I would never get a thing published. She has an unerring feel for language and is a

voracious reader. Once she retired she took to submitting my work, and that has been a godsend, because I despair at

the drop of a hat.

What are you working on now?

I'm busy scribbling in notepads and editing the fiction I've already written. In a sense I never finish anything.

I could go back into Far From Algiers and make changes, but would they be improvements? I've learned from painters

that artists rarely know which work is best. I have written three novellas, The Pain of Wearing Our Faces, Artemisia's Wolf

and of course Saraceno. The Pain and Artemisia are about women artists. Artemisia is an homage to Artemisia Gentileschi and

my Aunt Irene. I have been working since 1989 on a long novel whose title keeps changing as I keep editing and revising. I'm

not sure of its final shape, although it is essentially done. Perhaps it should be a duo or a trilogy. I'm undecided. I live

in this novel day and night. I dream of it. For a long time I called it Salvor's Deep. Then Diver's Angels. I hope to finish

revising it this winter. The Literal Latté winner is an excerpt from it.

Any comments?

If I've made a connection with any readers, they might wish to stay in touch with me by visiting my blog at

www.djelloulmarbrook.com. I post short essays and art with some frequency. I started it to promote Saraceno.

Now I hope it is promoting Far From Algiers. Over time it seems to have become useful for sorting out my thoughts.

This interview is one of a series conducted by Alexander J. Motyl

with Ukrainian Literary Night writers at Cornelia Street Cafe in New York.

Reprinted with permission of The Ukrainian Weekly

Alexander J. Motyl is a writer, painter, and professor.

Askold Melnyczuk, one of the leading fiction writers in the United States, is author of What Is Told, Ambassador of the Dead,

and the just published novel, The House of Widows (Graywolf Press). According to Jhumpa Lahiri, "Brisk, lyrical writing and a

winning narrator make The House of Widows irresistible. A son's quest to understand his father's suicide, and so to excavate a

family history extinguished by the exigencies of the new world, make it exceptional." Melnyczuk is interviewed by Alexander J. Motyl,

professor at Rutgers University and author of several academic books and two novels.

Motyl: Your latest novel, The House of Widows, has just appeared and received terrific reviews. Tell us how you came to write it.

Melnyczuk: The House of Widows has twin roots. The kernel of the novel came to me while reading the (Ukrainian) literary critic

Yuri Luckyj's memoir, At the Crossroads. In one paragraph he speaks about serving as a translator for the British military as they

interrogated Soviet prisoners-of-war, as well as deserters from the Soviet army, in Braunschweig, Germany. The soldiers largely

cooperated with the British because they thought they'd be allowed to repatriate to the west. Instead, after getting what information

they could from them, the British returned the soldiers to the Soviet army. Many of them were subsequently executed or exiled.

And Luckyj, who had by chance wound up in England at the start of the war, found himself in the morally intolerable position of

participating in this duplicitous project. He knew he was sending many of his countrymen back to certain death and he tried explaining

this to his superiors, to no avail. One of the chapters of The House of Widows uses a sentence from his book as an epigraph:

"Was I completely unable to stop this terrible traffic in human lives? At first it seemed so…."

Luckyj's passage occupies no more than a paragraph or two in his memoir, but it stayed with me. I tried imagining how this must have

felt for a kid of no more than nineteen or twenty, whose own father had already been arrested by the Soviets, how helpless he must

have felt.

Anyway, years after reading this I began working on a book about a man who has a similar experience and who eventually commits

suicide as a result of all that's set in motion by his early betrayal. The chapter, written from the Ukrainian-British soldier's

point of view, came to me in one afternoon's work-unusually for me as I tend to rewrite endlessly and fall into the category of the

writer as word-squeezer. But then I console myself that that phrase was coined by my literary hero, Gustave Flaubert.

That part of the novel which considers the sex trade is, and not just by the way, intended as a reflection on the implications of

an unfettered free market in which humans have long been treated as commodities.

The other moral thread of the story appeared years later, while I was traveling through Germany and Austria on a book tour for the

translation of my first novel. In Stuttgart, after a (rather poorly attended) reading, several of us went out for dinner. Present

was a young Caribbean woman who said she was working with American soldiers stationed in Stuttgart who were either deserters or trying

to get Conscientious Objector status to keep from being sent to fight in Iraq. She said there were some eight thousand young American

men and women around the world trying this gambit. I hadn't heard about the phenomenon. Back in the States I asked the great American

historian Howard Zinn about it and he said he'd heard such stories but didn't have any reliable headcount. Body counts aren't the only

thing our military avoids. This was a little while after the Abu Ghraib scandal broke; after some of the atrocities committed by our

soldiers in Fallujah had come to light.

Again I began wondering about the implications of this-not about committing the atrocities themselves, or about deserting,

which raise rather different moral questions-but about what it meant to know, to be given definitive information, about war

crimes. What responsibility did the average, only moderately engaged citizen have? Where did his first allegiance and

responsibility lie? Should a citizen conspire with his government in covering up the truth of wartime atrocities? What

good would it do to let the world at large know about them? Whom might it help? Whom might it harm?

Motyl: What answers did you come up with?

Melnyczuk: I was, as I said, interested in the position of the more-or-less average citizen and not of the active perpetrator

of the atrocity because that was the position I feel many of ourselves find ourselves in. We've read and heard stories about

actions we'd never be able to sanction under normal circumstances. Don't we have a moral imperative to do what we can to let

others know about them? Here I imagined what it might have been like to know about the Holodomor or the Holocaust while they

were underway. Didn't any honest woman or man possessing privileged information about these crimes against humanity have an absolute

obligation to act on them? If you see someone being murdered on the street in your neighborhood, aren't you obliged to do something?

What, in our global village, are the boundaries of our neighborhood?

Motyl: Those are exceptionally demanding moral claims.

Melnyczuk: I know. Of course we are all steeped in "mitigating circumstances." We have our own lives to attend to, our own daily

battles to struggle through. How much risk should a whistle-blower assume? What kind of risk were we talking about anyway?

In this context I remembered the phrase "the good Germans," which has enough currency to serve as the title of a popular film and

which is an ironic reference to the average citizen's quiet complicity in his government's criminal behavior. Are we, American citizens,

suddenly in that position ourselves?

So many other questions follow from this. For example, isn't "criminality" a relative concept defined by social institutions, courts,

and governments? Or was there a deeper, more reliable moral ground for asking this question? Here we skirt dangerously close to

metaphysics….

Motyl: How does a novelist answer these moral questions?

Melnyczuk: A novelist's way of examining such questions is by observing the behavior of his characters, by learning from them how

they act in the particular circumstances in which they find themselves trapped. Fiction, the novelist John Gardner observed, is an

ancient mode of thought. Story-telling isn't simply a way of passing the time-it's another way of trying to understand the human

meaning of time itself.

Motyl: In addition to morality, all your novels explore history and identity-and especially Ukrainian history and identity. It's hard

to avoid concluding that these issues are of deep emotional and spiritual importance to you.

Melnyczuk: History and identity are endlessly interesting. Another way to think about them is as cause and effect. A child is born

into circumstances it did not create. It is given a name by a mother and a father who both have their own past bearing down on them.

They live in a country that's at peace or at war. They grow up amid great wealth, or poverty, or somewhere in between. At the same

time they have something in them that doesn't seem to depend on external matters, on causes and conditions. What is that? The clash

or meeting or dance between that inner self and external circumstances creates what we call character. History and identity define a

part of the self-but all of us recognize we share a humanity that transcends any humanely created boundaries.

My own identity included the terms Ukraine, the Famine, the Holocaust, and all the abundance, beauty, and yes, ugliness, of New Jersey

in the second half of the twentieth century bleeding into the twenty-first. Each term in the above sentence can be combined in a

thousand different ways-writing fiction allows me to perform chemistry experiments using them as ingredients.

Motyl: What did you conclude from these experiments?

Melnyczuk: What I've found is in many ways obvious: that the elements interact differently in every individual; that there is enough

overlap in some cases for people to accept certain group affiliations; and that there are enough differences so that no generalization

about any group can be absolutely true and consistent. Where a sociologist or even a historian might be eager to identify and stress

common tendencies and broad categories, the fiction writer, like the poet, chooses instead to stake his claim to truth on specificities.

Creating my characters, I know they don't stand for or represent anyone but themselves.

You know, I grew up in the States at a time when certain generalizations about Ukrainians were commonplaces both in the media and

the classroom. They left me as furious as generalizations about African Americans or Hispanics-more, maybe, because I naturally felt

implicated in the often ugly broad stereotypes. On the other hand, if readers are to find them interesting or believable as characters,

they will need to see something of themselves in these fictive beings. Characters earn our sympathy when we can see something of

ourselves in them, no matter where we come from.

These days I confess I love reading history at least as much as, or maybe more than, fiction. Well-written history so often

reminds me that there are more things between heaven and earth than are dreamed of in our philosophies and that our imaginations

have to work overtime to begin to approach the complexity of "reality."

Motyl: How do you write your novels-with a clear outline in mind when you begin, or with a general sense of plot and

direction and character?

Melnyczuk: An image, an idea, and/or a character plant themselves spring up, usually without invitation. Most wither after

a scribbled page or two. Occasionally a seed finds fertile ground and gradually grows into a story; the gestation process

can take years. Did you know that an amaryllis seed is the size of a dime and that it takes seven years for it to become

that fat bulb sold in supermarkets across the country, ready at last, to bloom?

Scenes gather slowly; I revise and revise. I once spent three years writing 20,000 pages of drafts for a novel that never came

together. But that is part of the job description. Then, every so often, a story or a chapter (or a poem) comes quickly and I

grab them with a prayer of thanks.

My wife Alexandra Johnson, a far finer writer than I (fortunately she writes non-fiction), reads everything I write. I shudder to

imagine what horrors I'd send out into the world if it weren't for her generously critical gaze. I shudder anyway.

Motyl: You began writing as a poet, didn't you?

Melnyczuk: Yes, like so many fiction writers, I began as a poet. I still read a lot of poetry, and some of my best friends are poets.

But I found that in my poetry I wasn't able to find a way to get at certain questions and certain material that kept gnawing

at me-fiction offered a release into a larger realm of imaginative possibility. Yet I value poetry immensely for its ability

to get at essentials, for the way it probes the implications and possibilities of language itself. As a rule we use language

loosely; we take it for granted. In many ways, of course we should and we must. E. M. Forster describes how surprised a friend of

his was to discover that she had been speaking "prose" her whole life. In fact, all of us speak prose; very few of us speak

poetry-anymore.

Motyl: How did growing up Ukrainian influence your writing?

Melnyczuk: Both my mother and father are great readers. While my father prefers to immerse himself in history, politics, or

economics, my mother still, at eighty-seven, reads deeply and widely in what was once called belle-lettres. From childhood she

fed me a diet that included among its staples not only all the Ukrainian classics-Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, Lesia Ukrainska,

Olha Kobylianska, etc.-but also the great Europeans: Rilke, Lagerloff, Hamsun, Mann, Hesse, Gide, Rolland, Zweig. I was ten when

she gave me Rilke's Stories of God, a book inspired by his travels across Ukraine (which he of course called Russia).

I loved reading (and memorizing poetry) from childhood on. When I was six I recited Shevchenko's Poslaniye before two hundred

patient auditors at the Ukrainian National Home in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Never mind that I didn't understand a word-not a

word-of what I was saying. The roar of the crowd made it seem worthwhile. The habit stuck. And in high school literature

became a lifeline, offering a secret company of kindred spirits when none were to be found in one's immediate neighborhood.

I still remember the morning-it was four a.m., July, 1972-when I finished reading Gabriel Garcia Marquez's A Hundred Years of

Solitude. I put the book down on my desk, went out into the quivering predawn stillness, looked up at the stars, and saw them

as if for the first time. Literature re-enchanted the world for me. It reminded me of what most children know, and adolescents

too often forget-that we live in a world steeped in mystery, and that anyone who claims to understand it is posing, deceiving

both himself and the rest of us. Socrates' main claim to fame was the willingness to admit that he knew nothing. Gaugin's most

famous painting is aptly titled: Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? Art is possible because there will

never be a definitive answer to these questions.

Motyl: Which writers influenced you most?

Melnyczuk: So many writers enlarged both my sense of the world and my awareness of art's possibilities. A short list of predecessors

might include: Saul Bellow, Gregor von Rezzori, Ernest Hemingway, Rilke, Hamsun, and Alain-Fournier.

At the same time, one's contemporaries and peers can become catalysts in one's development, and I was very fortunate to have come to

Boston at a time when the city was enjoying something of a renaissance. I profited enormously from the company of friends like

Sven Birkerts, Tom Sleigh, Derek Walcott, Seamus Heaney, Tom Bahr, Ha Jin, Jason Shinder, and others-in many cases they showed me

just how high the bar stood; their example was an inspiration to keep pushing at the limits of what one could do.

They were courage-teachers, too.

Motyl: What led you to found Agni-one of the most prominent literary journals in the United States?

Melnyczuk: Agni was founded as an underground newspaper in Cranford, New Jersey by a group of grumpy, pissed-off, and

bewildered adolescents. My father loaned us $35 for a mimeograph machine and we began running off our little samizdat

venture. It's funny, my father was both strict and conservative but he was a deep believer in freedom of speech, and so

he supported the venture despite the trouble it got us into with school authorities. I will always be grateful to him for

that, along with so many other things.

When I went to college I took the name of that newspaper and slapped it onto a literary journal I printed up myself.

From 1972 on, I took the journal with me wherever I went. In 1979 I left the States to travel in Europe and the journal

was kept alive by Sharon Dunn. Later I took it up again and stayed with it until 2001, when I left Boston University to

teach at the University of Massachusetts. By then I had fully tasted the pleasures of editing. Along the way the journal

acquired a reputation-and it provided an enormously useful lens for viewing the contemporary literary world both here and

abroad.

Motyl: Agni was also remarkable for publishing so many Ukrainian writers.

Melnyczuk: That's right. My position as editor also gave me a ready venue for publishing Ukrainian literature in translation

during a time when many American intellectuals claimed no such thing existed. But it's harder to argue with facts on the ground

than with words in thin air. So Agni became a showcase not only for my own translations of Mykola Rudenko and Ivan Drach and

Vasyl' Barka but also those of Michael Naydan and Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps and later Jim Brasfield's translation of Oleh Lysheha

made its appearance in our pages, along with Halyna Hryn's translation of Oksana Zabuzhko.

It was working with Agni that brought Ed Hogan to the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard where he discovered a new literature

that inspired him to publish the ground-breaking anthology From Three Worlds.

By the way, there's a nice irony in that the journal now occupies the offices of the defunct Partisan Review, once one of the

America's leading literary-political magazines and which was founded to serve as a mouthpiece for Trotskyites. Who knows who'll

one day occupy Agni's offices? The world turns….

Motyl: How did you get involved with the writing scene in Ukraine?

Melnyczuk: In 1990 I received, out of the blue as it were, an invitation to attend a poetry conference in Kyiv called

Zolotyy Homin. That was an axial year in Ukraine's history-I happened to be there when the statue of Lenin was torn down

from in front of the Opera House in Lviv. In fact, my first day in Lviv I went to look at the Opera House, where my mother

used to go when she was a student at Ivan Franko University, before the war aborted so many lives, when suddenly I saw hordes

of people pouring into the square. Before I knew it I was pressed flat against the door of the theatre, listening to,

mirabile dictu, a speech by Father Andrij Chirovskyj, whom I had last scene at Plast Camp some twenty years before

(the rest of my Plast adventures belong in the memoir I'm currently writing).

At that conference I met not only those Ukrainian writers whose work I'd translated, such as Drach and Rudenko

(on whose behalf I'd written letters for Amnesty International-I bet Agni was the only underground newspaper in

America to run an editorial about the Helsinki Human Rights group and Rudenko), but also important émigré writers

like Bohdan Boychuk, Bohdan Rubchak, and Yuriy Tarnawsky. Moreover, I met the new generation of writers, and they

were hugely exciting. You could tell at once they were onto something big. The twenty-something Oksana Zabuzhko

was brash, illuminating, even intimidating; Yurko Andrukhovych was quieter, more inward, but you could tell that they,

along with Petro Midyanka and Sashko Irvanets and Viktor Neborak and others, were breaking new ground in their culture.

You sensed the borders of the motherland would not contain them, their spirits were already reaching out to places they'd

never been. And now they're nurturing a new generation of writers and artists to continue the conversation, this time on

the world stage.

Motyl: Who are your current favorites?

Melnyczuk: I've been moved and impressed by the poetry of Marjana Savka, Serhii Zhadan (through the Tkacz-Phipps translation),

and Vasyl Makhno. Recently I was blown away by the emotional force of Marjana Sadowska's singing. It's clear the culture's on

solid ground, and is now deeply embroiled in a vigorous conversation with the rest of Europe, and the world. Now if only

these writers were to find the support both in Ukraine and among the Ukrainian émigré community enjoyed by, say, German or

Irish writers, well, then we'd have more to talk about.

Motyl: Are you in touch with these writers?

Melnyczuk: I've stayed in close touch with Zabuzhko, have intermittent contact with Andrukhovych, recently came to know

Marjana Savka-I've no doubt the conversations will continue-unless one of us becomes a Trappist….

More recently, in 2003, I attended a conference in Kyiv on American literature organized by Dr. Tamara Denisova.

Walking into a classroom in Shevcheniko State University and listening to young (some remarkably so!) scholars

delivering papers-in English!-on Jamaica Kincaid and William Styron and others, was deeply moving. They underscored

something that's often overlooked when Ukrainian writers complain they're slighted in the West, and that is that culture

is a conversation, not a monologue.

Motyl: What's your next project?

Melnyczuk: My current project is a memoir, which includes an account of my time living at the Studite Monastery outside

Rome… and maybe a few words about Plast, too. But maybe not.

Author Bio:

Eric Wasserman was born and raised in Portland, Oregon where he attended Lewis & Clark College. He holds an MFA from

Emerson College and is now an Assistant Professor at The University of Akron, where he also teaches in the Northeast

Ohio Master of Fine Arts program in Creative Writing. He is the author of a collection of short stories, The Temporary Life

(La Questa Press, 2005). His short story, "He's No Sandy Koufax," won First Prize in the 13th Annual David Dornstein

Creative Writing Contest, and his work has appeared in or is forthcoming in many publications, including Glimmer Train,

Poets & Writers Magazine Online, Michigan Quarterly Review, Vermont Literary Review, and Istanbul Literary Review. His

story "Brothers" was the winner of the 2007 Cervená Barva Press Fiction Chapbook Prize. Eric has recently completed his

first novel, Celluloid Strangers. He lives in Ohio with his wife, Thea. Visit him at www.ericwasserman.com.

The room I write in:

I write in the back office of my apartment. It wasn't much until my incredible wife, Thea, decided I needed to make it my own.

I am surrounded by movie posters and books and mostly write on my Mac, although I do all editing by pen on printed manuscripts

(that's the real writing for me). To the right of my desk is an extra chair with a pillow for my cats to sit on and look out

the window, captivated by squirrels outside as I work. I am surrounded by pictures of those I love, both living and dead. And

I have a replica of Michelangelo's statue of Moses as inspiration for the new novel I am working on. I also have plenty of

file cabinets since I never through anything away that I write and always print out drafts, then more drafts, then even more

drafts, and drafts and drafts and drafts. I'm a multi-tasker, which my wife admires, but it drives her crazy when I am

writing with the music cranked up as loud as it will go (if we ever buy a house she's insisting on sound-proofing my

future office). I am not one of those people who can write in a coffee shop and I never write by hand (only edit by pen

on what's typed). I prefer having my known space, my apartment office. If I go to a coffee shop I am going to have a nice

time and enjoy good company and good talk. I am sure there are exceptions, but I get the impression that people who write

in public are in love with the idea of being a writer instead of embracing the writing life. I hope I am wrong about that.

For me, if you want to be a writer you need to be quite secure and content spending massive amounts of time by yourself

bringing your imagine worlds to life on the page. For me, that place is my home office. Besides, I can't bring my cats

to a coffee shop.

Some (I stress "some") of the writers who have influenced me and why?:

To be honest, I think writers are influenced by everything they read. In fact, I don't read to have my sensibility of the

world reaffirmed; I am struck more when I'm challenged by a different perspective. And I have probably been influenced just

as much by what I don't connect with because it shows me what I don't want to be doing as a writer. So, if I gave you a genuine

list it would be exhausting.

That said, I should say that if you had to simplify things, my greatest influences remain Salman Rushdie, Philip Roth and

Mikhail Bulgakov. All of these writers possess the "what if?" factor in their fiction. To be honest, I like minimalism in

doses but I've never seen the great attraction to it except for Carver and the few others in his top shelf class. I am looking

for possibility in fiction, and I am not a reader who needs completely grounded realism. I love hyper-sensitized realities in

which the author is pushing the world we know to the limit of believability to make a profound point. If you look at

Rushdie's The Satanic Verses, Roth's The Counterlife, and Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita they are all doing that.

Also, when you talk about influences a writer must look at writers and their body of work, not just individual gems.

I don't like everything these writers do, but holistically they all captivate me and I want to keep reading them because

I never know what I'm going to get as a reader. I can't say that for other writers. Also, I am somebody who appreciates

language because I think it matters just as much as story and Rushdie, Roth and Bulgakov all seem to be able to bend

language to their very will in ways that I am continually awed by. I would also like to say that there are specific books

by individual writers I continually go back to. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Ernest Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms,

Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried, and most recently Cormac McCarthy's The Road are very dear to me and probably

always will be.

How long have I've been writing fiction?

I'll place the number around fifteen years, if you are talking about being serious about it. I've always been a storyteller.

That's the kind of family I have. We thrive on stories and I have been making them up my entire life. But I would say that I

have been writing fiction seriously since the summer after my freshman year of college when I turned 19. That's when I began

writing my first novel that hopefully nobody will ever see. Since then it's been an integral part of my life. But the creative

impulse was set in me from birth; I've always had it.

Talk about your collection of short stories, The Temporary Life (La Questa Press, 2005).

The Temporary Life was always imagined as a collection. Even the stories written that didn't make it into the book were components

of a greater whole. I have always seen my work as part of a larger picture anyway. Occasionally I will write something isolated but

I always have a larger book project going. Even "Brothers" refused to remain self-contained, it eventually became my first novel, at

least the first novel I am proud enough to publish and not hide away in a drawer. The Temporary Life was actually conceived in the

summer of 1996. I took a writing workshop from Jordanian-American author Diana Abu-Jaber and the title story grew out of an exercise.

Before then I had completed a worthless 250 page novel manuscript and I was basically writing what I thought I should be writing

instead of what I wanted to put down. Naturally, I've been a great consumer of Jewish-American literature, but other than

Philip Roth I couldn't say I ever really saw myself in the majority of the Northeastern-centric fiction on Jewish themes,

and in fact I don't always see myself in Roth's worth either. However, when I mention him and Rushdie and Bulgakov as my

greatest influences it really is because they give me access to their worlds in a way that I can imagine myself living

within them, and that's rare.

The Temporary Life set out to present west coast Jewish-American life as I hadn't seen it in fiction. If you read a lot of

Jewish-American fiction you might get the impression that all American Jews are from New York City or New Jersey or Boston

and that our parents all retire to Florida. I don't know that world. I know a diverse west coast experience I was raised in

with cities such as Seattle, my hometown of Portland, Sand Francisco, and especially Los Angeles all having their own unique

Jewish-American sensibility and quirkiness. I wanted to capture that in the stories in The Temporary Life.

That said, while I am incredibly proud of the book, I would never write those stories today. Those are stories written by a

man in his twenties with a very different outlook on life. Today I am not the man who wrote those stories, but I am glad they

are there. Beyond the content of the stories, I can look at them now and see a young writer who was very hungry to make his

mark. And while some of the stories no longer hold up, they all have an immediacy and energy to them that I think only youth

can bring to fiction. I sort of miss that immediacy but I would never want to again be the writer who created those stories.

However, I recently did a short reading and decided to read the first few pages of one of the stories from the book and it was

nice to revisit those characters and feel that sense of being a writer in his twenties again. Now that I am in my thirties I

am hoping I can look at The Temporary Life the way I now look at one of my favorite movies, Richard Linklater's Before Sunrise.

I saw that movie when I was very young and said, "That's me!" Now I watch it and think in a bittersweet way of who I once was and

how that film reminds me of how I once saw the world and who I thought I was going to be.

Your short story, "He's No Sandy Koufax," won First Prize in the 13th Annual David Dornstein Creative Writing Contest.

Talk about this story.

That story is in fact the one I recently read the opening of to some colleagues and graduate students. Every self-respecting

writer has a baseball story in him, right? In the June 12, 1999 issue of Sports Illustrated there was an article titled

"The Left Arm of God" by Tom Verducci, who is one of the smartest sports writers in the country. The story really got me thinking

about a lot of things. Sports are very important in my family and I was honestly never any good at them. I just didn't have the

natural ability my brothers had except for modestly succeeding as a high school wrestler, but that's another story. I was so bad

at sports when I was a young boy that I actually pretended not to like them at all when I really did. Looking back, I guess it was

a defense mechanism of sorts; if I sucked at sports I could chalk it off to the fact that I supposedly just didn't like them. And

it worked because I had this incredible creative impulse whether it was Legos, or drama club, or music and movies.

When I was in college my father still had season tickets to the Portland Trailblazers. I didn't see my parents a lot but I remember

those games I would go to with my dad as being very special. It was when we really spent time together and when I think I finally

got to know him as an adult, get to know him as a person. That Verducci story made me think of how a lot of fathers I grew up around

talked about sports. My dad was raised in Los Angeles, and since Portland, Oregon didn't have a major league baseball team we kind

of routed for The Dodgers by default. I have always been interested in symbolism, how people see things for more than they really

are; what's under the surface. And I've always been interested in who people say their heroes are. And heroes change. When I was a

teenager my hero was probably Stephen Spielberg because I was obsessed with movies, but that's not the case any longer. I wanted to

write a story about how things can mean so much to certain people for very personal reasons but nothing to others. The main

character in "Koufax" is not my father. The story does have little bits of pieces of personal family history, but so far very

few have caught them. Mostly, I wanted to create a character who identifies so strongly with a public figure but resents that

others don't see the profound qualities in that figure that he does.

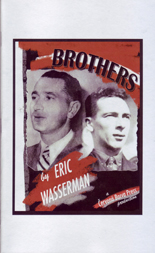

Your story, "Brothers," won the 2007 Červená Barva Press Fiction Chapbook Prize. It has just been released for publication.

Where did the story come from?

It is very loosely based on a true story my buddy John Zamparelli told me. The real story concerned two men who were not brothers

and it was an Italian-Catholic community in Boston, Medford in the fifties if I remember right. The story just really captivated me;

it was quite cinematic, especially the way John told it since he comes from a screenwriting background. I had just come back from

Los Angeles, where my family is originally from, and I have always been fascinated by history and how place becomes a part of our

own little personal histories. I essentially took the gist of John's story and instead made the men Jewish-Americans brothers in

the late 1940s. Aside from the general situation of a guy coming to tell another guy to step down from a job he's

always dreamed of, the story is completely fictional. Still, I like to think that the spirit of the original story

John told me is inherently there in the chapbook. Also, at the time, which was early 2001, I was writing these short

pieces of domestic fiction and I needed to do something different. I've always loved stories that blend genres.

I think of "Brothers" as a domestic story, but one that incorporates classic literary crime fiction elements in

the tradition of, say, Dashiell Hammett's The Maltese Falcon or Eric Knight's You Play the Black and the Red Comes up.

Your wife, Thea Ledendecker, a graphic designer, designed the chapbook cover, where did the photos come from?

The two men on the cover are my grandfathers. One of the nice things about publishing with a small press, beyond the personal

attention you get, is that most small press editors are generous and open to the ideas their writers have and will listen to

them. Sometimes those ideas are shot down, but they are at least respected. Thea came up with the basic concept for the cover

of my first book of short stories. I am a consumer of family history and love old pictures. I never expected that Thea would be

allowed to design the chapbook cover completely, I thought she would just be able to point the press in the direction I saw

fitting, as she did for my first book.

The process was very organic. I am not a visual artist, but I know what I like. I made some horrible pencil sketches of a

few different ideas for the cover. The most important part was that I really envisioned the cover of the chapbook being an

homage to those wonderful pulp B-picture cinema posters from the 1940s, the time period the story takes place in. Unfortunately,

movie poster art has become a lost craft because these days you can just use a still from the production. One might also notice

that the dialogue in the chapbook is quite different than the style in the stories from my previous book. I didn't want to mimic

the dialogue of those old movies, but I took it as my starting point, the terseness, the directness in the delivery. And since

the movies are so important to the story of the chapbook and the novel that eventually grew out of it, I thought the cover

should capture that. For my first book Thea used many of my old family photographs. For this one she took one of each of my

grandfathers from around the period. And since my two grandfather's didn't necessarily see the world eye-to-eye I got a kick

out of the idea of them sort of representing the two estranged brothers in the story. I was a little worried about using the

pictures of my grandfathers, but I sent my mother Thea's early mockup and she loved it.

Right now you are working on editing your novel, Celluloid Strangers.

How many pages is it now? You said you cut 100 pages. I don't want you to give away the story,

but could you talk about your writing process for this novel.

Actually, I just finished a new draft of the book yesterday to send off to my literary agent and it clocked in at

566 pages including the appendixes, which is intended as fun extra reading if anyone is interested. As I said, the

novel grew out of "Brothers." I had no idea I had a novel there, I thought I was just writing a short story, but it

became larger. There's always a danger of overwriting for me. For my wife, it's the danger of underwriting, not

layering the story. I layer far too much in my drafts. But I need to have everything on the page before I can do anything

with a story or its characters. The rough draft for "Next Year In Kona," the first story in my book of short fiction, was

over fifty pages long. I had to break it down to its bare essence and it was a gratifying experience. The manuscript for

Celluloid Strangers reached over 1,000 pages at a point. "Brothers" was probably a good third longer in its original

form than what it now is as a chapbook. And yes, it was overwritten, but I am the kind of writer who needs to go through that

process.

The novel required a lot of research, several years worth. Although several historic events and peoples are mentioned in it,

select dates and circumstances were altered or fictionalized for narrative purposes. Historic accuracy was never intention;

it's not a factual social or political history. It represents a hyper-sensitized interpretation of the "spirit" of the times

and events surrounding Old Hollywood and the House UN-American Activities Committee. The thing I always had to remember is

that the story is what matters. I could only use maybe 20% of my research. In fact, I am going to be leading a session in

November at Bowling Green State's Winter Wheat Writing Festival about how to incorporate research into a fictional narrative.

I'm really excited about the novel, but it's been a long, laborious experience writing it, and my head is already into my next

book. But that's how I work, while I am writing one book I am already taking notes for the next project.

You teach at The University of Akron as an Assistant Professor and in the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts program in

Creative Writing (NEOMFA). What do you try to teach your students about writing?

I think writing programs are really in a transitional moment and there is something exciting about that and I'm proud to be a

part of it. Creative Writing courses have unfortunately been seen as fluffy electives where students emote and there is little

craft analysis. I pride myself on giving students a grounded vocabulary with which they can deconstruct their own work. I am

not a literary theory wonk by any means, but a general understanding of it can save a writer years of trial and error that I

went through. Having a basic understanding of narrative space, content control and the delicate relationship between the author,

narrator and characters of a story will move students beyond this fallacy that they go off into the world and "live" then sit

down at a keyboard and everything pours out perfectly in one spit. Writing is labor, period. Revision is what I stress most,

probably because that's my real joy, where my stories truly come to life.

There are of course things that I can't teach students. I can't teach them discipline. I can encourage it, but I have given

up expecting them to all write from six to eight in the morning every day and cram in any spare time available, as I do. I

also can't teach them the blessings that failure provides, I just hope they can learn that on their own. The writers who have

even a modicum of success are the one who refuse to take no for an answer. If they are rejected by a journal, they send right

out to another one. If they have to accept that the story they are working on was a good effort and might not work the end,

they push on to write a better one. And they do this over and over and over again. Anybody can want to write, but the obsessive

need to do it is just there or it isn't.

And I try to explain to students that we're all in this together. Just the other day I got an e-mail from my literary agent

saying that my novel was rejected by a publisher I would have been happy to go with because, even though they admired it,

they could not conceive of a way to market the book. There's the crummy bottom line in publishing at work again. People studying

writing must learn to have faith in their own stories and not jump on trends because they think it's going to get them published.

Blacklisted screenwriter Lillian Hellman once said, "I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions."

That's a pretty good motto to live by as a writer. I've always written whatever I wanted to and probably always will. Sure,

I've missed some opportunities because of it, but I don't care. Writing is not like being a young actor and being forced to

take whatever roles you're offered and then beg for the next one in auditions.

Finally, I have to roll my eyes when I hear people telling writers to "find their voice." I have no idea what that's supposed

to mean, never have. The very act of writing itself means you have a voice and are using it, period. Shaping it, chipping away

the rough parts, that's another story, but the voice is already there in all of us simply by making the choice to put

words down.

What difficulties do you see in today's colleges and universities regarding writing classes and programs?

I think the debate over the validity of writing courses and writing programs has become incredibly juvenile. It serves nobody.

How about some constructiveness to make writing studies great; wouldn't that wonderful? Last year AWP invited a writer to speak

at its New York City convention who I once heard in a radio interview severely ridicule writing programs. Obviously AWP forgot

the "Program" part of its title. I heard from several people that this writer came for twenty minutes or so, was smug and

arrogant and left. The truth is that not everyone is made for a writing program and writing workshops. They work for some

people but not for others. Generally speaking, if you have experienced the process of disciplining yourself in some way,

whether that's sports or music or dance or whatever, you will do well in a writing workshop because you know that criticism

of your work is not personal, that you can understand what somebody is saying when they tell you, say, You're character

development is great but that there is little transformation in the person.

Some of the difficulties are in student preparation. Students certainly want to write but they don't necessarily want to read,

and that is the major problem. As it is apparent, I am obsessed with movies, but I read just as much, probably more. If you're

looking into writing programs, I highly suggest opting for one with a strong literature component. And ignore the ranking and

prestige of programs. Choose one that is right for you. Also, I think people should think twice about entering an MFA program

directly after finishing their undergraduate work. In some cases, it's definitely the right move, probably more so for poets

from what I have personally seen even though I can't be specific as to why, it's just a general observation. I took three

years off between college and graduate school and I know it was an asset because in those three years I had go-nowhere jobs

but I was constantly reading and writing. For a fiction writer, it's very difficult to create real and complex characters if

you don't yet know who you are as a person. But that's also an asset to young writers in classes and programs. You have so

many chances to try out different styles and approaches, like when you're young and are trying out different identities and

wardrobes until you know which one is the genuine you. I like to have my students look at just the first page of

F. Scott Fitzgerald's This Side of Paradise and compare it to the first page of The Great Gatsby. The novels are five years

apart but it's as if two different writers wrote them. Paradise is, as my friend Bob Pope would say, a beautiful mess of

a novel. But when you read Gatsby you are reading a novel written by a man who perhaps finally knew who he was as a person

and could then more intimately know who his characters were as people.

However, the biggest difficulty in classes and programs is that we need to be far more honest when it comes to the expectations

our students have. There is a trend of professionalizing writing programs and I tend to be in favor of it. Yes, I want students