|

July, 2005

Aug. 2005

Sept. 2005

Oct. 2005

Nov. 2005

Dec. 2005

Jan. 2006

Feb. 2006

Mar. 2006

Apr. 2006

May 2006

June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

October 2008

November 2008

December 2008

February 2009

March 2009

April 2009

ČERVENÁ BARVA PRESS NEWSLETTER

Gloria Mindock, Editor Issue No. 45 May, 2009

INDEX

Welcome to the May, 2009 newsletter.

I would like to thank everyone who donated to the press and bought books during our April fund-raiser. Bill and I are so grateful.

This will help us continue with our publications. We are a very active press so the donations were appreciated!

Cervena Barva Press Reading Series

Wednesday May 20th at 7:00PM

Pierre Menard Gallery

10 Arrow St., Cambridge, MA.

Readers:

CL Bledsoe/ Reading from Anthem, Cervena Barva Press, 2009

Sam Cornish/ Poet Laureate of Boston

Nancy Mitchell/ Reading from Grief Hut, Cervena Barva Press, 2009

Hope to see you there.

New poetry chapbook published April 28, 2009:

Balancing on Unstable Ground by Francis Alix

Francis Alix's Balancing on Unstable Ground employs all the reader's senses – the poems bleed and chirp and thunder and exude odors

both foul and fair. Through unstinting depictions of war and spent love, Alix chronicles what could be the end of things, but, with

an alchemist's pen, transmutes them and us into a vivid way forward "on the wings of foraging birds."

- Lisa Beatman, author of Manufacturing America: Poems from the Factory Floor

Reading Alix's work, I am reminded of this line from the song, Jungleland, by Bruce Springsteen, in which the lyrics protest,

"And the poets down here don't write nothing at all, they just stand back and let it all be," frustrated that poets have somehow

abdicated their responsibility by averting their eyes, but more importantly, their words from the struggles, triumphs and drama

of everyday life. Alix has been recording life as only he can see it, our world seen through poetic eyes, unafraid to see the

harsh realities and capable of sparkling revelations. He has been busy down here, knee-deep in a poets work, bringing our

attention to the glories and cruelties, through poetic stories only he can tell. Whatever the subject, Alix slices to the

heart of it, as only a poet can do. Springsteen is wrong. There are real poets down here, refusing to let it all be.

Francis Alix is one of them.

-Eileen D'Angelo, Editor Mad Poets Review

New poetry chapbooks coming out in May:

- Opuscula by Steve Glines

- The Possibilty of Recovery by William Delman

New poetry full-lengths coming out in May:

- CL Bledsoe (Anthem)

- New Play by Michael Nash called They're Dropping Bombs Not Ham Sandwiches

- JAROMÍR HOREC (Anežka Ceská/Agnes of Bohemia)

Translated into English by Jana Morávková Kiely

Cervena Barva Press, Gloria, and Bill are moving!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

There will be no newsletter in June. We will be sending

a newsletter out in July.

You will be able to order books online and do business as usual. As far as correspondences and e-mails, I will get back to

you when I can. We will be quite busy and have tons of books to move as well as the usual furniture etc...

What a huge chore! Please be patient. Once we're settled into our new place, we will once again start working on books.

I will be writing all authors in July with a publication schedule. Please wait until you hear from me. Thanks again.

Wish us luck on this!

Congratulations to Cervena Barva Press authors Nancy Mitchell and Catherine Sasanov. Nancy's book Grief Hut and

Catherine's chapbook, Tara, both published by Cervena Barva Press, were named favorite new books by

Dzvinia Orlowsky in The Bloomsbury Review, Vo. 29/Issue 2. Mar/Apr 2009. Thank you Dzvinia for picking these as two

out of three for favorite new books.

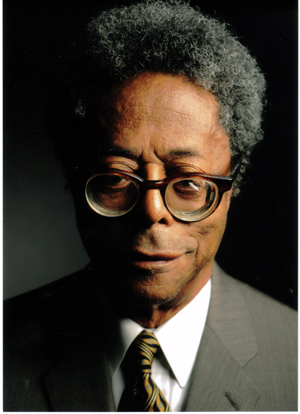

Interviewed this month: Sam Cornish, interviewed by Mignon Ariel King

and Alfred Nicol, interviewed by Amanda Mooers.

Please check out Burton Watson reading from his Late Poems of Lu You at www.poetryvlog.com

Thanks Jesse (Ahadada Books) for sending it to me.

Truth in Poetry: Interview of Boston Poet Laureate Sam Cornish

by Mignon Ariel King

On a wind-chilled but sunny day in Copley Square, Boston, the Poet Laureate Sam Cornish sits in his office with his coat on.

I am not late, nor are we going outside, yet he looks ready to go someplace important. Mr. Cornish is in some ways the definitive

quirky artist, a native of Baltimore who was influenced by but never quite fit into the Beat Generation or the Black Arts Movement,

race and class preventing a complete sense that either might be his community, a place to settle in.

The Laureate, however, is not truly flighty; he is focused, practical, communicative, self-aware, and his refreshingly old-fashioned

qualities ground him in the present even while making him seem from a bygone era. The old-fashioned charm is worn as loosely as his

overcoat--which it turns out he is simply carrying on his shoulders for later. We do not discuss either the highly-recommended

"Generations" (1971, Beacon Press) or his newest collection "An Apron Full of Beans" (2008, Cavan Kerry). This is a man of

dialogue and observation, not self-promotion.

KING: How long have you been writing poetry, and what got you started?

MR. C: Oh, thirty to forty years. Reading literature and writing in general came first, then poetry. I read the Moderns and the

Black Arts Movement poets, Eliot, Barack, [Langston] Hughes....

KING: Were there other writer heroes in your early years? Who are your heroes now?

MR. C: {He smiles, seems surprised at the question:} Ah. I was into Kerouac, Cummings, Margaret Walker, Gwendolyn Brooks.

Now I like Mary Oliver, Dickinson, of course, a lot of locals, like the Ibbetson Poets. I think Lisa Beatman's very good.

And Glo Mindock, Elizabeth Quinlan. {He adds me to the list here, and we digress for a brief conversation about how he thinks

I am like a Harlem Renaissance writer and Beat writer rolled into one but also part of the "New Age" of Boston poetry, a

multicultural age. I suddenly feel as if he's read my diary. Including and knowing artists are his missions.}

The big boys of Boston--Bidart, Pinsky, those cats--as accomplished as they might be...well, they don't seem to be part of the world

we live in. Small press poets seem to be 'real'. I've got a thing for local multicultural poetry [and international poetry].

It's necessary [for poetry to thrive]. It's got to be gay/straight, men/women, poor too...a lack of pretention--none of that

poems-in-the-garden stuff or, what I'm really tired of, the middle class supposedly suffering without time to write. Oh, boo hoo.

It doesn't embrace poor people's suffering. [That's why I appreciate] the small press, and poets like Doug Holder and Harris Gardner.

I don't know anybody else like that! You walk through your kitchen and there are 10 e-mails on your computer from those two

[about upcoming poetry events and other literary news]. Activism.

KING: Do you identify as a Black or African-American poet? And what does that really mean in 21st-Century America, especially

considering the protest tradition? {I earn another gold star of a smile for this one. He shakes his head in approval.}

MR. C: It depends. It all depends--on what perspective I'm writing from. Like many African-American writers, I have a dual heritage,

at least. European, African, American...I'm all over the place. You know. I like "Free to be you and me." Unfortunately, well,

maybe just circumstantially, the European influence is most powerful. [Partly because of] how some

writers dealt with it. Let's just say Ralph Ellison WAS Black versus "wearing Black." [And]

I'm tired of fabricated nastiness nowadays, people thinking it goes along with their poetic images. They come to your house

as fellow writers, then steal your books, or they leave you with a big bar tab. I'm talking about men here, entertainers too.

Spoken worders. Hip hop!

KING: I'm glad you mentioned that. How do you think Black written-word poets can remain relevant in a

spoken-word generation? Why is this important?

MR. C: Black male poets should be socially-minded as well as literary. These hip-hoppers, with them it's one word after

another, the [spoken-word] poets do it too. It is rhythmic, attracts attention, an audience. It's an audience that moves

but doesn't want to think. I'm slow moving, but have a quick ear. {I look up, and he smiles, just seeing if I was

listening.} It's word-driven, but the content! It's important because there should be some family history and social

responsibility. There's a lack of historical and social depth. [Add those elements] and you could bring that energy

into the classroom and bars [where they have poetry slams]. Young people can relate to truth and honesty in poetry and

come to it, especially problem kids. It's nice for them to have someone write a poem about something they can relate to.

Problems. Overcoming. Dennis Lehane comes to mind.

KING: Do you think the divide between Black men writers and Black women writers has really narrowed significantly since,

say, the Harlem Renaissance or the '60s Black Renaissance? If not, what strategies might close the gap?

MR. C: Whew! It's probably wider. Men complain they can't publish while Black women get published all the time. {I laugh.}

Well, a bit more, but for good reason [having nothing to do with racism]. There's a thing called human sexuality, then there's

just nasty. Some Black male poets write great stuff, then they have to add...let's just say it is a little nasty and shows no

respect for women. {We concur that we don't want to read that either.}

They could have a wider audience. {He sounds more wistful than scolding here.}

KING: Why are you the poet laureate of Boston, specifically? What's so thrilling to you about this city,

personally and professionally?

MR. C: As a kid, I had too much hair, bad feet, patches, liked to read. In Baltimore that meant "gay [lots of homophobia then],

dirty, strange...." Bad enough in general, but in the Black community--I know you know!--I got, "What's wrong with that boy?!"

In Boston I found a home, a community instead of just a few individual poets here and there. The Carpenter Poets do it for fun

and have a sense of community, and Harris [Gardner]!!

Poetry Marathon? Who else has a poetry marathon? In the Cambridge area too. The poets are very supportive, more

open and accessible [than Boston's academic poets.] I get to feel like a person. [They accept change too.] Change

is for the better [in the arts].

In many ways, the poet laureate position is the best thing that ever happened to me--outside of discovering whiskey and music.

{He pauses, pleased with himself as I am cracking up.} Before that, I'd stay away from writers, groups of writers.

I thought they were all pretentious.

KING: Last question. Do you believe in or have a muse?

MR. C: [Laughs.] No! [Thinks a moment.] Kinda yes, kinda no. I believe in God and notebooks. I mean, I carry my

notebooks in case something comes from someplace unexpected, suddenly. I guess something's out there. I'll have to

change my answer to 'yes'--but not in a conventional sense.

He holds doors as we leave the cafe of the Boston Public Library and pauses to appreciate and snap a photo of the lovely

courtyard garden as if he didn't see it regularly. The most fascinating aspect of interviewing Sam Cornish is that he was

interviewing me back the entire time, subtly, just getting to know me. He is very obviously interested in people, especially

those who make up his adoptive city, so much so that he weaves them into the historic and literary traditions of Boston in a

manner that is simultaneously warm and analytical. Sam Cornish is the first poet laureate of Boston, Massachusetts.

Our city has a reason to be very proud of its important new directions.

How did you first find poetry? Or did it find you?

I knew very early on that I wanted to be a writer. I mean very early on, before I could read. A neighbor

sat in her front yard reading a picture book of Moby Dick to her son and I looked over her shoulder.

The drawings excited my imagination immeasureably. I never forgot the experience. I began trying to

teach myself to read by saying the letters of a word so quickly that they began to slur together. My

method doesn’t work, of course. “Cat” would be pronounced “Saty” if it did. The point is that my earliest

literary experience was not in the least abstract; it was altogether physical. The picture of Ahab lashed to

the whale seared itself into my mind. Then I began my own literary work focusing intensely on the

sound of the names of letters, mistakenly believing that I could figure words out that way. I certainly did

learn from my error. If I’d had a teacher to show me the right way to go about it, I’d have missed out on

that intense physical encounter with the written word. That’s poet’s work.

Though both of my parents made education a high priority, neither of them had had much of it. My

mother did not attend high school. My father was asked to leave his sixth-grade classroom for some bit

of misbehavior and he never went back, though he did later receive some technical training at the high

school level. But my mother would kneel beside me at bedtime and recite the Catholic prayers in

French; that was a lovely verbal music that stays with me just out of hearing. And my father had a good

singing voice. He sang around the house all the time. When I first heard a CD of Hank Williams’ songs

only about 10 years ago, I realized that I knew all of the words to all of the songs. They were the songs

my father sang. That’s not a bad first influence for an American poet —rather like a Scottish boy listening

to Robert Burns.

Again, with all of these early influences, it’s the sound of words that worked on me. There’s also Dr.

Suess, who is a delightful poet and ought to have a volume in The Library of America series. And the

first record album we had around the house, which came with the stereo my parents bought: Nat King

Cole. I became a shower-crooner myself imitating him.

Who are the poets you read again and again? Do these poets influence your current work and if so, how?

I guess it should come as no surprise that one of of biggest influences is not a poet per se but a writer of

songs, Bob Dylan. His work is of vital importance to me. Another poet for whose work I feel a great

affinity is Philip Larkin. Both of these writers use rhyme to great effect. But they have something else in

common. Both are willing and able to bring “negative emotion” into their work. Too many contemporary

poets write as though they are trying to please an audience; they say things that people want to

hear. Certainly a lot of gloomy poems get written, but they are generally written about political or social

issues on which there is widespread agreement, at least within the literary community. It’s safe to be

angry in the abstract about something that all your friends are angry about. Or despondent in the

abstract. But Dylan and Larkin both express emotions that are not particularly attractive. Dylan will

come right out with it: “You’ve got a lotta nerve / to say you are my friend.” And Larkin’s entire body of

work cries out: “I am a lonely man, and it’s my own fault: I chose this life, and I would choose it again.”

You may not want to take either of these men as a role model, but it’s enormously freeing to have their

work as an example. If I’m not at least a little close to the edge in the act of writing, I find the writing

loses energy.

Starting out as a poet, some of the first poets who mattered to me were Denise Levertov, Robert Creeley

and Robert Duncan. I envied the obvious friendship of these three, which did not exclude honesty; they

could be very critical of each other’s work. Now I’m lucky to have a group of poets with whom I share

the same kind of intellectually honest relationship, The Powwow River Poets. I can’t believe my good

fortune. I’m almost reluctant to admit that Bill Coyle, who is a younger man than I, is someone I’d list

with Larkin and Dylan as among my favorites. But when our workshop rolls around on the second

Saturday of the month, I walk toward the library anticipating something new and wonderful from him.

And Deborah Warren will be there, Rhina Espaillat and David Berman, Bob Crawford, Len Krisak,

Midge Goldberg and Mike Cantor. They are the best group of people anywhere; I’m glad to be included.

The discussion is not limited to that one Saturday each month. We exchange poems via email all the

time. Richard Wollman sometimes sends me two or three poems a week! Wollman’s own work is strikingly

like that of Eugene Montale (without his having been consciously influenced by the Italian poet), and

not much like my own. Maybe for that reason we’ve been particularly helpful to one another as readers.

He’s had a major hand in helping to revise some of my own best work, including the title poem of my

next collection, “Elegy for Everyone.”

You worked in printing for twenty years—why the move to poetry?

Believe me, printing was never an alternative to poetry. Poetry is a calling; printing was a job. My first

son was born while I was still in college. I needed to make a living, and I thought --mistakenly, as it turns

out--that if I took an artisan’s job I would be able to write in the evenings, not having to “take my work

home with me.” I did not realize how drained I would feel after a long day in the shop, how much of my

time and energy would need to be devoted to raising my children. I’m proud to say that I became a very

good printer, and I feel as though bringing up my two sons is the best work I’ve ever done. I was not as

successful in trying to write all those years, though. I did keep it up almost all the while. I stopped at one

point for almost two years. Since consciously deciding to “be a poet” in my sophomore year of high

school, that is the only time in my life when I did not write.

I certainly had no time to spare for “po-biz,” though. I published only a handful of poems over the two

decades. In the late nineties, a new press at The Maryland Institute College of Art agreed to publish a

book of mine titled “Ask.” The book would have been an art object itself, printed on an old Heidleberg

letter set press. I saw the proofs, but my heart sank when I saw the mistake the students had made in

backing up the pages incorrectly. Had they folded those signatures and put the book together, half of

the pages would have been upside down. It was back to the drawing board, and since the students who’d

done the work had graduated, the work couldn’t begin again till fall. By then another editor had taken

over, and he decided in favor of another manuscript, so mine never got printed.

In October of 1998 I was able to “retire” from printing and devote my time entirely to writing. The “Life

of Riley” is essential to poetry. One can industriously go about writing a book of fiction or non-fiction,

researching, setting up time charts, travelling to find out about specific locales. Writing poetry is largely

a business of waiting around for something whose arrival you cannot be sure of, listening in silence to

silence. One can appear very lazy doing this difficult work. Poetry is less like industry than it is like fishing,

patiently waiting, risking the waste of time. Or like gardening, except that the seed-packages are

unmarked. You can do the planting but you never know what’s going to come up! Lucky me, at least I

have something to show for the nine years I’ve spent courting the muse. My first book, Winter Light, was

published in 2004. An anthology of poems by the Powwow River Poets, which I edited, appeared in

2006. And a second book of my own, Elegy for Everyone, is supposed to be published in the next few

months. It makes it easier to justify such lack of industry. As the son of a factory worker, my unconscious

(and so inarguable) definition of what makes a man has a lot to do with hard work, so this is something

I take quite seriously.

Where do you write? Explain your writing “process”.

That questions follows nicely from what I just mentioned, my idea that a man has to go off to work in

the morning. When I first left printing I began a routine of arriving at the Newburyport Public Library

as soon as it opened in the morning. I would sit there surrounded by books and force myself to write for

several hours “by any means necessary.” Once I even grabbed books down from the shelf and copied

one phrase from each --whatever phrase caught my eye-- to make a poem:

Hymenaeus & The Scholar

Coffee. Different

marriage proposals to read.

His commitment to

reason had scrawled above it,

“Tendency to disappear.”

Terribly crowded,

and if the answer is two,

(“My love, don’t fail me–”)

he needed a few more days,

a ten-minute walk, these lines.

It would be absurd

to hope for that. A murmur

of talk, rendezvous,

windows of a pastry shop.

His pretty, freckled wife. Go

on, all the lights in

the paintings, her small hand

on Sundays after mass, rich,

“the result of emotions,..”

“Dear Elena,” he began.

The whole poem is in italics because every word of it is stolen from a book in the library. A lot of what I

did at that time was experimental. I wrote to keep writing.

I remember Diane DiPrima telling me when I was a young man that one must write stream-of-consciousness

for months to write off the top layer and get to the good stuff underneath. That had long been part

of my “method.”

After a few months I rented a small apartment. That way I could get tea without interrupting my writing.

I didn’t have to wait for the library to open. If I felt tired I didn’t have to quit for the day; I could nap

for twenty minutes. Or I could write all night long if I felt particularly inspired.

But I still approached my work in poetry the way I’d approach any other work. I didn’t wait around for

inspiration. I’d noticed that those lines that came to me in the night and demanded to be written, which

I’d find later scribbled on little scraps of paper on the nightstand, were really no better than lines I took

absolutely for granted as I worked hard at my desk in the daytime. I was learning something that I later

found perfectly expressed in a poem by X. J. Kennedy, which I have by heart:

On Being Accused of Wit

No, I am witless, often in despair

At long-worked botches crumpled, thrown away—

A few lines worth the keeping, all too rare.

Blind chance not wit entices words to stay

And recognizing luck is artifice

That comes unlearned. The rest is taking pride

In daily labor. This and only this.

On keyboards sweat alone makes fingers glide.

Witless, that juggler rich in discipline

Who brought the Christchild all he had for gift,

Flat on his back, with beatific grin

Keeping six slow-revolving balls aloft;

Witless, La Tour, that painter none too bright,

His draftsman’s compass waiting in the wings,

Measuring how a lantern stages light

Until a dark room overflows with rings.

That poem of Kennedy’s is my ars poetica. It’s a fine corrective to all kinds of soft notions about how

poems get made, and it’s especially helpful to someone whose self-worth is so directly tied to the idea of

“doing a job right.” I haven’t grown out of being my father’s son.

Tell me about your move from the Beats and free verse into formalism.

Poems like the one I showed you, “Hymenaeus & the Scholar,” are formal poems, though they’re not

traditional poems. They’re formal in that they obey a set of a priori rules, rules that someone else could

follow in writing a similar poem. The rules for that particular poem are simply that each phrase that

enters the poem has to be the first phrase that makes itself legible as the poet scans through a library

book at random. It’s a silly kind of form, but it’s a form.

Any game that has rules is a formal game. The difference between a game of tag and just running

around in the schoolyard is that there are rules for playing tag. I’ve always loved the game of baseball

with its near-perfect set of rules. I quickly lose interest in a game where the rules are set aside for any

reason at all.

No one in the world would have referred to the poems I was writing ten years ago as “formalist” poems.

But the formalist imagination was hard at work all the time, working too hard, I would say now, reinventing

the wheel time and again. The rules for writing a sonnet are quite as beautiful as those that

govern the game of baseball, and one can invent any number of different games without coming close

to creating one nearly as good.

Generally when people speak of formal verse now they mean metric verse, of course. Blank verse is a

pretty open-ended “form” but we would consider any poet who wrote blank verse to be a formalist.

It’s actually a shorter leap from the Beat poets to metric poetry than it would be from typical lit-mag

main-stream free-verse to metric poetry. Ginsberg’s father, Louis Ginsberg, wrote and published traditional

metric poetry. He recited Milton aloud at home. Ginsberg himself was keenly aware of his (albeiteccentric)

poetic lineage. When I attended Ginsberg’s class at Naropa Institute he used as his texts

poems by George Herbert and Thomas Nashe. William Blake and Christopher Smart were more important

to him even than Whitman; the lines of “Howl” owe a great debt to Smart’s weird wonderful poem

“Jubilate Agno.” Ginsberg was never “winging it” as a poet. He didn’t mistake the imperative to “break

the iamb” as a call to forget about meter altogether.

The other poets usually grouped under the rubric “Beat” are hardly free versers of the sort one reads in

today’s literary journals. Gregory Corso, wildest of all, taught himself to write by reading Shelley and

Keats in prison. If you think he was not concerned with meter, read his long poem “Bomb.”

Kerouac himself read the Bible and Shakespeare ceaselessly.

To me, these writers don’t represent a break with the tradition. I don’t think they saw themselves that

way either. Ginsberg for one seemed positively obsessed at times with locating himself within a poetic lineage.

I picked up that obsession from him. Right from the start I’d make long lists of my poetic “ancestors.”

It’s a boyish self-aggrandizing thing to do, but fun. And it does at least make you aware that this

art of ours isn’t a recent fad.

As an aside, I’ll show you a metrical, rhymed poem on which Ginsberg and I collaborated back in 1975.

I say that we collaborated; actually he wrote the last line for me when I showed it to him and complained

that it didn’t finish the way I’d planned for it to finish. He got my meaning exactly right.

Pilgrimage

The purpose of the sage

Is pilgrimage,

Like dust to alight

Upon the sacred stage

And beg the Mercy of a Might

Whose single breath of rage

Could waft the man from sight.

This path I trust.

Should the Deity

And I agree,

His death must

Prove His sympathy

And all return to dust––

May God then hold His breath for me.

The Black Mountain Poets, who have their own section in Donald Allen’s famous anthology that included

the Beats, were more intent on “breaking the iamb.” Charles Olson was no sonnetteer. But Robert

Creeley’s early poems have a very formal, song-like feel to them. They sound like Thomas Campion

updated. Listen to this one:

The Way

My love's manners in bed

are not to be discussed by me,

as mine by her

I would not credit comment upon gracefully.

Yet I ride by the margin of that lake in

the wood, the castle,

and the excitement of strongholds;

and have a small boy's notion of doing good.

Oh well, I will say here,

knowing each man,

let you find a good wife too,

and love her as hard as you can.

How long a leap is it, really, from a poem like that to the kind of poem that I try to write? I would like to

think it is no leap at all. One poem that I originally wrote in imitation of Creeley later needed only a

couple of changes to get published in The Formalist magazine edited by William Baer.

I always did apply a kind of “measure” to my verse. For years my way of writing involved a kind of meditative

focus on the intake of breath; I would then type whatever words came to mind while “breathing

out.” It was like crossing a zen practitioner with a saxophone player. It’s a good way to keep your writing

from getting too “heady.” It gets the whole body involved. You write from the solar plexus rather than

from your intellect. That’s awfully important in writing poetry. Poetry suffers as it gets farther away from

dance. Pound said something to that effect. Well, you need your body to dance.

The problem with using one’s breath-pattern as a “measure” in writing poetry is that the breath-pattern

changes depending on the emotional state of the poet. I found it awfully hard to re-enter poems in

order to revise them when I wrote that way. Ginsberg’s “First thought / Best thought” dictum enforces

itself under those circumstances, because if you go in and make changes, they often sound out of place.

You’re not in the same state of mind; you’re breathing differently today than you were yesterday. The

“measure” changes.

I began to experiment using a measure that could be replicated; I began counting syllables. Kenneth

Rexroth, a west coast poet who’d been something of a mentor to the Beat poets, wrote most of his poetry

in syllabics. The lines of his poems were usually either seven or eleven syllables long. I’d written some

of my earliest poems in high school this way in imitation of my first poetry-hero, Dylan Thomas. His

great poem “Fern Hill” is a syllabic poem, though not all the lines are of the same length.

I felt like an apostate even adopting that rudimentary “outside” structure. At the time I was thoroughly

persuaded that form in poetry should be “organic,” as Denise Levertov put it. It had to come into being

as the poem was composed; any pre-existing form was an antique. The poem ought to take shape the

way a tree takes shape as it grows; you mustn’t pour a poem into a mold.

It all sounded convincing because so much of it is true, all except the assumption that to write a sonnet

is to pour a poem into a mold. Any sonnet that works as a sonnet is a poem that found its way into that

shape as it was being written.

Anyway, I hope that the lessons I learned over so many years of reading the Beat poets, the Black

Mountain poets and the San Francisco Renaissance poets have carried over into the kind of writing that

I do now. Certainly the habit of letting the breath be instrumental in shaping the line stays with me;

there’s only the added tension of playing that energy against the meter. Sometimes the line that I

“breathe out” is shorter or longer than a line of iambic pentamenter. That creates a caesura partway

through the line, or an enjambment that carries the breathe through two or three or more lines.

Allen Ginsberg himself showed me how to read Milton by inhaling whenever a comma appeared. It’s

great fun. Sometimes that will slow a line down to a snail’s pace, there’ll be a comma after nearly every

word. Other times it would require a saxophonist like Sonny Rollins to do it right because the breathe

extends over many lines. Here’s Satan getting tossed out of heaven. Try reading it Ginsberg-fashion, only

pausing to inhale at the commas:

Him the Almighty Power

Hurld headlong flaming from th' Ethereal Skie

With hideous ruine and combustion down

To bottomless perdition, there to dwell

In Adamantine Chains and penal Fire,

Who durst defie th' Omnipotent to Arms.

I’m afraid I’m trying to say too much all at once. It’s funny how important all of this remains for me.

But getting back to what I began to tell you, I began to write syllabics and had success with them. I

found that I was able to return to a poem the next day or several days after I began writing it and pick

up where I’d left off. I was able to complete more ambitious projects. And it didn’t hurt that every poem

that I wrote in syllabics eventually found its way to publication.

When I first attended a Powwow River Poetry workshop, I brought along one of my syllabic poems. It

was pretty well received by the other poets, among them Len Krisak, a former student of J. V.

Cunningham. Cunningham’s uncompromising opinion equated real poetry with metric verse, and I

think it’s fair to say that Len shares that opinion. When I had read my poem to the group, he remarked,

“Not bad for free verse.”

Well, that got my back up. For me, a poem written in syllabics was the height of formality. As time went

by I heard similar disparaging remarks about free verse from Len. I decided to show him! My intent was

only to write a single poem in one of his antiquated meters, then go back to writing free verse. I used a

poem by Emily Dickinson as a metrical template and wrote one of my own. (Ironically, Dickinson is the

very poet that Ginsberg had recommended that I read.) Here it is, my first consciously formal poem:

Empty Streets

I went out on a holiday

In Berkeley, once, alone.

Most everyone had gone away.

The sidewalks were my own.

And I had nowhere left to go––

I’d put the world behind me.

I hid out in the open so

That nobody would find me.

The sun, even, had other plans

And did not come to shine.

My shadow was another man’s.

These shadows all were mine.

And I was happy, in a way,

My world was just this size.

There was no clutter in the grey

For me to organize.

I am alone. I am alone––

Who says this suits me well?

The voice I heard was not my own,

But no one else could tell.

My plan of attack backfired on me. It was supposed to be a hit-and-run job. I was going to write just the

one metrical poem and have done with it, but I found it so pleasant to work in meter that I’ve never

stopped since. Meter and rhyme to me were like wonderful Christmas presents, the best gifts ever. I’m

forever playing with them.

What do you feel formalism allows you to achieve that free verse doesn’t?

To oversimplify, as everyone seems to do when this topic is broached, formalism allows me to know

when something I’ve written is a poem. For years and years I wrote poetry, line after line. I have notebooks

filled with the stuff. I never had a good feel for when a particular poem would begin, or where it

should end. Louis Zukofsky said that “A man writes one poem all his life.” That was almost too literally

true in my case.

At least, if you are writing a sonnet, for instance, you know that it will end at the end of the fourteenth

line. Of course, if you have any understanding at all of the form, you realize that a sonnet has to accomplish

certain things before it gets to the end of the fourteenth line. So the pressure’s on. It’s like a basketball

game when the clock is running down. The play becomes more intense. The players play with

more energy. Poetry is all about getting as much energy as possible into as few words as possible. Any

technique or tool that helps charge words with energy is worth keeping around.

You can take some pride in learning to use the tools well. It’s a good place to put pride. It won’t do to

be proud of your “inspiration;” that’s taking credit for what the muse brought you. You don’t own your

gifts. Your muse is likely to abandon you in a huff if you pretend not to need her.

But you can take pride in hard work, in putting to good use the tools available to you. That’s the message

of the poem by X. J. Kennedy that I showed you. Once you’ve become adept with the traditional

techniques of poetry, you can use them to great expressive effect. Listen to what Kennedy does in the

twelve line of his poem. We see the juggler flat on his back before the Christchild, “Keeping six slowrevolving

balls aloft.”

Now, by line 12, which is the one I’m quoting here, the iambic pentameter has worked its way into the

reader. Something in the reader has come to expect the 5 beats per line, the steady ta-DUM ta-DUM ta-

DUM ta-DUM ta-DUM under the more complex changes in the spoken language. But in this line, by substituting

a troche for an iamb in the first foot, and substituting a spondee in the second foot, he surprises

us wit a line that reads DUM-ta DUM-DUM ta-DUM ta-DUM ta-DUM. A poet or reader who is familiar

with iambic pentameter knows that both of these are allowable substitutions: they don’t “break the

meter.” That’s to say the line is still a line of iambic pentameter, but a line of pentameter with six stresses.

Kennedy has accomplished precisely what he tells us the juggler is doing, keeping six balls aloft. An

effect like that is only available to someone working in meter. When working in free verse, a small metrical

change can have very little effect on the reader because no expectation of pattern sets up the expressive

break in the pattern.

Working in meter allows for countless expressive effects like the one I’ve tried to describe. It gets a little

technical trying to describe them, so I won’t go on in that vein any longer. I’ll only say that these effects

are abstract and technical only in one’s description of them; they are utterly physical when they happen

upon the reader. It’s not an intellectual thing. Most readers are probably not even aware of what hit

them, but if they have any sensitivity at all, they know they’ve been hit. The line I’ve quoted is taken

from a very moving passage. Kennedy’s sophisticated use of meter helps to charge the language with

meaning.

“Technique is the test of sincerity,” is the way Ezra Pound put it. That’s almost the exact opposite of the

assumption that many young poets bring to the art. They believe that considerations of technique get in

the way of really expressing themselves, of letting it all out. What Pound is telling us, what Kennedy is

showing us, is that language can only get at meaning on a deeper level through technique.

It’s almost a cliché for people to say that poetry is an oral art form. Do you agree? Do you write for the page? Or do

you write poetry intended to be read aloud?

I write poetry to be spoken by an ideal voice in the mind of the solitary reader. That sounds pretentious,

I know, but I think it describes exactly what is going on when I most enjoy poetry as a reader myself. I’m

not a big fan of poetry readings, to be honest. I truly believe that my “ideal reader” --whom no one has

ever heard, of course-- does a better job of reading Yeats’ poems aloud than Yeats himself. I suppose the

best argument for poetry readings is that you may hear something in a poet’s way of reading that later

becomes part of the voice you hear inside your head as you read. The ideal reader picks up an accent

sometimes, and sometimes it sticks.

The best poetry performers, of course, are singers. They don’t always have the best poetry to work with,

but they certainly make the most of it.

Confessional poetry—what are your feelings about it? Who or what do you write for? Are there limits for you as a

poet when it comes to disclosure?

Well, lyric poetry is expressive poetry. Like nearly all contemporary poets, I am by and large a lyric poet.

(That’s to say I’m not writing epic poetry, I don’t generally write dramatic monologues, I rarely write

narrative poetry that isn’t a kind of narrative/lyric hybrid.) So I write poetry meant to express emotion.

Songs for the page, more or less. And whose emotion am I able to express, really? My own.

That doesn’t mean that I’m locked into my own little world, that I can’t empathize with anyone else. It’s

just that, if you hurt and make it known to me, and I empathize with you, I don’t really “feel your pain,”

as President Clinton used to say. I feel some new pain of my own, the imagined equivalent of your pain.

Tolstoy is very good on this subject. He is a master artist painting on the broadest canvas imaginable. He

brings an entire world alive. But to hear him talk about it, you realize that “War and Peace” might justifiably

be titled “Song of Myself.”

The Song of Miss Lily

Miss Lily has a hollow face,

A hollow face has she.

And when I see Miss Lily’s face

It always frightens me.

I remember Lily’s face

When she was just a lass.

And is that not Miss Lily’s face

I see within the glass?

That is a poem of mine about a woman’s fear of growing old, her sense of loss. Naturally I’m not so

keen on getting older myself, so it’s easy to feel something like what she must feel, and sing the song of

it in her voice.

I suppose “confessional poetry” is poetry written in the first person where the “I” really seems to be the

poet himself. But the self at any given moment, self-perceived, is a fiction. “I” is always another, as

Rimbaud said. The poems of mine that a reader would be most likely to assume are straight from the

heart, just naked statements of the way I feel, make use of every bit as much artifice as any of my other

poems. What happens is that I sing the song of one clear emotion selected from the usual tangled mix

in my heart. Yes, I really feel that way, but only fleetingly; a number of other emotions and considerations

give the lie to the one I choose to let stand alone in the poem.

I Go Near Love

I go near love advisedly.

Someone is there, expecting me.

She may not be as mindful, though,

Of consequence we cannot know––

With loss the only certainty.

She pictures love a tranquil sea.

I know how cold its depths may be.

Love is a place I would not go:

I go near love,

Where, looking in her eyes, I see

The soft flame burning quietly,

And my brief wings beat to and fro

About that mesmerizing glow.

Though I may fly I am not free:

I go near love.

Every word of that poem is true for the moment of the poem. But when you hear me say, “Love is a

place I would not go,” you can be sure that “I” is another.

Probably the nagging concern that people have about confessional poetry is not that the poet reveals

too much of himself; it’s that he reveals too much of the lives of those around him. It’s unseemly to

invade someone else’s privacy that way. “My wife’s manners in bed / are not to be discussed by me.” And

there are other things I might want to keep to myself.

Most great lyric poetry is written about things the poet might want to keep to himself. What’s essential is

that those things undergo a seachange, a transformation, in coming across the threhold into the poem.

Poems aren’t made to spread gossip. They’re made to tell “the news that stays news,” as Pound put it. If

“I is another,” so too is the lover of I, toward whom he expresses his longing in a poem. She’s not the

actual person with whom he makes love and argues, she’s been lifted into art. Lifted into art, and now

she is someone with whom the reader is on familiar terms. No need to invade her privacy. I is the reader,

her intimate.

I often worry that my poems may appear “unseemly.” I often experience a sense of shame as I step down

from the stage at a poetry reading, as though I’ve revealed something that should have remained hidden.

Ultimately, though, I think that really translates into a concern that I haven’t served the art well

enough, that I didn’t make real poetry happen, the sea-change didn’t come about.

Self-Portrait

Isn’t it rich of me

To write and then revise a poem

About leaving you

After sharing a cup of tea

And resting in your company,

Entirely at home

Deceiving you?

Do you consider yourself a regional poet?

No, but I think other people decide that sort of thing, if they care enough about a poet to want to claim

the poet as their own.

What do you read for prose?

Oh, I read a lot of prose, though I don’t read quickly, so “reading a lot” doesn’t mean I get a lot of reading

done. Right now I’m reading Flannery O’Connor. She’s wonderful. Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead was a

very fine book that I read recently. I also try to read something written in French every day, often something

by Georges Simenon, though right now it’s a book called “Monsieur Ibrahim and the Flowers of

the Koran.” Every so often I read a fat history book. The French Revolution by Charles Downer Hazen,

in two volumes. Lincoln by David Herbert Donald. Things like that, books that I’d have found terribly

dull at other times in my life. Now I find them centering. In books like those the words mean just what

they mean on the surface. It’s not an edgy experience to read them, as it is to read poetry or fiction.

And every year I indulge in reading a book or two about baseball.

Tell me about your experience at Dartmouth. Did you have any mentors there? How did they affect you?

The best teacher I ever had was a man named Harry Schultz. He was well over six feet tall. His hair had

turned completely white when he’d been held prisoner by the Germans during World War II. When he

walked across campus you could see that shock of white white hair moving along above the heads of

other people. I studied Milton and the metaphysical poets with him. Though I admired him immediately,

it took us a while to connect. I was an unkempt and long-haired factory boy; I didn’t speak very well. I

may not have appeared to be a serious student. But nothing mattered more to me than the The

Tradition in English Poetry. An outsized young man’s ambition was kicking in my chest. He figured that

out and was very happy to be of use. He gave me a place to read, a wooden chair in his back yard beside

Occum Pond. He was going to be my thesis advisor. I was going to write about George Herbert and H.

D., religious poetry before and after Freud. I’m sure he’d have convinced me not to waste my time on

that wet-behind-the-ears Big Theme, to simply do close analysis of the poems, which is the only thing for

which I had a real aptitude. But my first son was born right then and together we decided to put the thesis

aside.

Syd Lea was teaching at Dartmouth when I attended. I saw him get into a terrific argument with a visiting

poet; Syd was defending the poetry of Allen Ginsberg. I signed up for Syd’s seminar on Wordsworth

and Wallace Stevens. He gave me the key to his research office in the Baker stacks. It is evident, looking

back, that Syd didn’t really buy into the teacher-student relationship where I was concerned. He considered

the two of us as young poets with something to learn from each other. He certainly treated me as

an equal, which was a pretty heady experience for me. He’s a friend for life.

Through Syd I met another young professor, Dick Corum. Dick was an important teacher for a number

of student poets there, including Louise Erdrich. He combined a laid-back California outward appearance

with a fiercely intense intellect. His way of reading was profoundly influenced by Freud. He’d bring

all of that to a close reading of a poem I’d written only the day before. It was terrifying. I was always

afraid he’d find out something terrible about me that I was unaware of myself! But it was a gift of untold

worth to have one’s poems taken so seriously. He was an extraordinary teacher.

Another person from whom I could learned a lot was Jay Parini. I’m afraid I wasted my opportunity. I

have indeed learned a lot from him, but only through reading his books. I kick myself for not having

gotten to know him better while I was at Dartmouth. I think I held a grudge against him for not admiring

the Beat writers sufficiently.

What advice do you have for young poets?

Read deeply.

Do you still write any free verse and would you ever publish it?

I have a number of old poems that I still have every intention of including in a book someday. I kept

them out of the book that will be published this year because the publisher, Alfred Dorn, is a man who

worked tirelessly for many years to promote metrical poetry at a time when it had fallen into disfavor.

He’s interested in publishing metrical poetry, so the manuscript I gave him is entirely verse.

If you would like to be added to my monthly e-mail newsletter, which gives information on readings,

book signings, contests, workshops, and other related topics...

To subscribe to the newsletter send an email to:

newsletter@cervenabarvapress.com

with "newsletter" or "subscribe" in the subject line.

To unsubscribe from the newsletter send an email to:

unsubscribenewsletter@cervenabarvapress.com

with "unsubscribe" in the subject line.

Index |

Bookstore |

Submissions |

Newsletter |

Interviews |

Readings |

Workshops |

Fundraising |

Contact |

Links

Copyright © 2005-2008 ČERVENÁ BARVA PRESS - All

Rights Reserved

|