|

July, 2005

Aug. 2005

Sept. 2005

Oct. 2005

Nov. 2005

Dec. 2005

Jan. 2006

Feb. 2006

Mar. 2006

Apr. 2006

May 2006

June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

October 2008

November 2008

December 2008

February 2009

March 2009

April 2009

May 2009

July 2009

August 2009

September 2009

November 2009

December 2009

January 2010

February 2010

March 2010

April 2010

May 2010

June 2010

July 2010

September 2010

October 2010

November 2010

December 2010

January 2011

February 2011

March 2011

April 2011

May 2011

June 2011

July 2011

September 2011

October 2011

December 2011

February 2012

April 2012

June 2012

July 2012

August 2012

October 2012

November 2012

February 2013

May 2013

July 2013

August 2013

October 2013

November 2013

April 2014

July 2014

October 2014

March 2015

May 2015

September 2015

October 2015

November 2015

August 2016

March 2017

January 2019

May 2019

August 2019

March 2020

April 2020

May 2020

ČERVENÁ BARVA PRESS NEWSLETTER

Gloria Mindock, Editor Issue No. 101 July, 2020

INDEX

July, 2020 Cervena Barva Press Newsletter

Finally, the warm weather is here and with the area now being in Phase 3 from the Pandemic, it is a little easier to be outside.

I would like to welcome my intern, Zachary Cook, from Lesley University. He is helping me with the

readings that celebrate 15 years of the press. He will be learning all aspects of the press.

I look forward to teaching and working with him.

It is exciting to have new books released this month. They are:

I am currently working on a play by Brian Arundel and poetry books by Mark Fleckenstein and Charles Cantrell.

These three books will be done this month and off to the printers. Also need to finalize a book by George Kalamaras.

After these books are done. I am taking one week off from laying out books. Then I will start again refreshed.

I have been working non-stop since January getting books out.

Hilary Sallick lives and works in Somerville, MA. She teaches reading and writing to adult learners and serves

as vice-president of the New England Poetry Club. Her chapbook, Winter Roses, was published in 2017, and her first

full-length collection, Asking the Form, was published by Cervena Barva Press in early 2020. Her long-time interest

in the potential of poetry to build community and to foster deep learning grounds all her work.

Says author Susan Donnelly of Asking the Form, "I very much admire the beauty, depth and intensity of this collection,

in which Hilary Sallick takes the materials of daily life and shapes them into profound meditations on life itself."

We spoke with Hilary about her journey as a poet and educator:

Q: What started you on your poetic journey? What called you to poetry? What was your most significant "poetic schooling"?

I think from childhood I felt the desire to put feeling into written language, but I didn't know this was what I wanted.

I began writing / struggling to write poems as a young teenager. As a college student, I enrolled in classes both in reading

and writing poetry, but the intimidating academic context was not helpful to me. Then, as a master's student at the Harvard

Graduate School of Education, I was introduced to Eleanor Duckworth's work on teaching and learning, and I began to put more

trust into my own mind and what it might show me. This made a huge difference for me, both as a writer and as a reader.

(For those who are interested, I recommend Duckworth's book of essays, The Having of Wonderful Ideas.)

Q: Tell us a little about your poetic practice-what inspires you to write a poem? How do you prefer to work?

Are you part of a writing group? When do you know that a poem is "done"? What are you working on right now?

Inspiration can be elusive, and my sonnet sequence "Asking the Form" suggests how a poetic form can be helpful

for the poet as she tries to find her way. I've experimented with the pantoum, villanelle, sestina, acrostics,

and found poetry, in addition to the sonnet; all of these have kept me going when I couldn't find the source I

needed, by giving me a structure to rely on.

These days, however, my poetic practice has evolved into what I think of, simply, as taking notes. There is a lot

of freedom in note-taking. It allows me to follow the feeling of what I see or think. And writing what I observe

helps me to pay attention - to anything and everything, to whatever I notice. This practice enriches my life. I

keep my notebook with me at all times, and I try to write in it every day.

It's interesting to open my notebook and to try to decipher my own scribbled lines or pages. I like then to turn to

the computer and to type what I find, culling and revising as I go. This work at the computer becomes the second

draft, then the third, fourth, fifth ... As you can tell from all I've said so far, I am an intuitive writer. I don't

usually know what I'm working on until much later.

When I have a draft of a poem, I need others to read it. I rely on my long-term writing companions,

Mary Buchinger and Linda Haviland Conte, as well as the New England Poetry Club Workshop and other

occasional groups. When I share a draft with fellow poets, I think of this as "testing out the poem."

What will happen when I read the poem aloud to listeners? How will I feel about it? What will they notice

and what will they make of it? What weaknesses will emerge and how will I use them as opportunities to further

develop the poem? I am not so interested in perfection as I once was. I feel that a poem is done when most of

its problems are fixed - or when I have decided its imperfections are somehow essential and unavoidable.

Q: Which poets, contemporary or otherwise, have most inspired you? What quality of their poetry speaks to you?

These days I have been reading Ammons. I am so moved by his poem "Easter Morning" and the way in which it travels

on the page and through the reader - with a kind of freedom (like those eagles it ends with) into such a deep place.

I also love the idea of a "transparent poetry" that Stanley Kunitz talked about and worked toward and created, the

idea of a clear, maybe even plain, language through which something can be seen. Other poets whose work is close to

me for one or more of these qualities of depth, freedom, and transparency are Emily Dickinson, Lucille Clifton,

Irena Klepfisz, W.S. Merwin, David Ferry...

Q: What other art forms or life experiences have informed or influenced your work? How does your work as an adult

basic education teacher impact your life as a poet?

I love to experiment with other art forms. Painting and music are two other media that help me to deepen my

attention and to see more. It can feel like a relief to work on something free of language, and what I learn

I can bring back into words.

Similarly, my work as a teacher gives an essential ground to my life as a poet. And sometimes it feels

continuous with poetry; my students and I look at things together - poems, stories, flowers, maps, whatever

we are studying - and we notice details and we keep looking. I learn so much from this experience with them,

and a community of love and learning develops among us. Right now, I very much miss working in person with my class.

Q: Can you tell us about your role as Vice-President of the New England Poetry Club (NEPC), and also describe

the work that NEPC does? What are some highlights of your time there?

I like to think of the New England Poetry Club as a learning environment for poets and readers of poetry.

I want the club to bring poets into deeper connection with their own work and with the work of others. How

can we do this? This is the question that our current board (Mary Buchinger, Linda Haviland Conte,

Wendy Drexler, Jennifer Markell, and I) regularly turn over and explore as we make decisions about our

reading series, open mics, contests, workshops, social media, etc. I think there aren't a lot of structures

in the world that exist to value and promote poetry, to connect people with poetry, so there's a need.

The club is a membership organization, but as the board developed and defined our vision, we agreed that

we did not want to be an exclusive or elitist group; this is why membership is open to any and all. We are

always working to extend that invitation.

I'm excited to see the club growing, and I'm grateful to be part of this community. One highlight for me was

Eileen Myles's reading at the Longfellow House last summer. Eileen's intensity of purpose inspires and thrills me.

The reading was an exciting event and brought many new members to our audience.

Q: How do you see NEPC and yourself within the literary community in the Boston area, the country and

internationally? What are your feelings about the state of "the literary community" right now, especially

in this time of global pandemic?

This is a hard question! I may begin to have an answer for you in another ten years, when I can look back

and see what is so hard to see when we're in the midst of it. For now, I'll just say that I think a challenge

for any community or "club" is how to develop a culture that is at once meaningful, grounded in something

shared, and at the same time open and growing. It's not easy. And I think this time of pandemic is creating

new opportunity for connection, even as it separates us from each other; it's wonderful to have readings

and workshops with poets across distances.

Thank you so much, Hilary, for answering these questions, and for the great work that you do!

Associate Editor, Liberated Voices

Nancy Ndeke, is a Poet of international acclaim and a reputable literary arts consultant. Her writings and her

poetry are featured in several collections, anthologies and publications. She has several published works,

including poetry, short stories and novels.

A collaboration of poetry with Prof Gameli Torzlo of Glassgow University, titled "Mazungumzo ya Shairi" is

her latest work, published in 2020 and registered with the Library of Congress, USA.

When did you start writing?

My love in and with writing is from the day I started reading, which I have done consistently from the age

of ten to date. An accident found me hospitalized for more than a year. To while time away within the hospital

walls, and since I was bed ridden, relatives would bring me story books, magazines (I particularly remember

the Readers Digest and its many stories). Upon recovery and eventual discharge from the hospital, I found the

reading habit had formed and stuck.

Back to school, and my essays and vocabulary seemed to impress my teachers. The consistent reading had

somehow paid off, and I wrote my first play at the age of fourteen which was performed at the end of the

school year. That first play, though not played at the National gallery was the most beautiful creation I

ever had as a gift. And I never stopped writing all the way through high school and college.

What is the writing scene in Kenya like?

Kenya is richly endowed with internationally acclaimed writers, majority of whom are in their sunset years.

However, the succeeding generation has not let the old guard down, except their focus has been primarily on

curriculum based writings against the backdrop of older writers that sought writings on a broader scale,

tackling themes of social injustice, poor governance and neocolonialism. The new breed of writers in Kenya

are doing fairly well and especially with and in poetry. There are writing groups that support writers with

ideas and I think this is an encouragement worthy of praise. I belong to a few.

Talk about your books, Lola-logue and Soliama Legacy

I wrote Lola-logue as part of a series based on a family set up and all the drama that has been known to

afflict families especially when a child is lost in unclear circumstances and the silent accusations that

often lead to the end of a marriage and further suffering of the surviving child/children. Of note, is the

need to have a common front in times of disaster to mitigate further agonies. Often, this does not happen,

and the result is what I used in this first book of the series to high light the ensuing struggles.

Soliama Legacy delves into the insanity of war and warring, the suffering of the people caught up in

such wars, the corruption that is the cause of war and the hypocrisy involved in the politics of those

who support warring. This is my longest book yet and goes to beyond nine hundred pages. Am recalling it

for re-editing and hope the lessons of cruelty of those seeking positions of power both in politics and

religious institutions, can be more humane in their pursuits.

How long did it take to write these book?

Soliama Legacy took about a year to complete. It has many harrowing experiences within it. One needs

longer breaks from writing such to avoid being sucked in by the events within the book and the various

characters one has to deal with. It has some pretty hard incidents bordering on horror.

Lola-logue took two months to finish the first series. The other three, and which are still unpublished

came easy because I was building on a known theme and familiar characters.

Like Mbizo Chirasha, you are also an activist poet. What was your time like in the war

torn South Sudan/ what did you do there?

I write about social issues. It's a subject close to my heart. From the plight of the marginalized people

living with disability, to domestic violence and bad governance. I address the interconnectedness of social

injustice which are never isolated cases but a part of the whole. An example is a woman losing a husband to

death, then relatives disown her and throw her out of her home with the children. Unable to meet the basic

needs of the children, she could end up in another abusive relationship, her children could fall out of school

and end up in the streets or worse join criminal gangs and use and peddling of drugs. Had the government

protected the woman, all the outcomes mentioned up here would have been mitigated. Cultural practices once

allowed to keep implementing their gender unfriendly and archaic rules is one of Africa's worst cases of

undermining equality and quality life. Female genital mutilation, child marriages as well as forced marriages,

denial of girl children from attaining schooling and many more come to mind. My writing, be it in short stories,

poetry or novels revolve around these issues.

In South Sudan, I worked with an NGO as a project manager. The NGO was dealing with a serious issue of street

children in the Upper Nile State of Bentiu. The project was sponsored by UNICEF but would also get food

donations from WFP and UNOCHA. This case of an influx of street children in the heart of South Sudan was

baffling even to the residents. This was because the South Sudanese families were closely knit and having

been at war for so long, it was an inbuilt reaction to take care of any and all children who had lost their parents.

These children brought a new aspect to the community that was unknown before. Once South Sudan had seceded

from North Sudan, all the Southerners were forced out. UNOCHA handled the case or returnees well, but along

with adult returnees were many unaccompanied children who ended up in the streets. Their stories ranged from

having mothers who had married a Northerner and who opted to stay in Khartoum but opted to send the child back

to the South. Others, were children born out wedlock and sometimes from mixed blood and who were not welcome

in the parents' home. The worst group were the ones who had been inducted into the military as child soldiers.

This category was unable even to trace where they came from and ended fending for themselves in the market and sleeping there.

Their plight is still unknown after the second civil war broke out and everything scuttled.

What social issue is close to your heart that you speak up about the most?

INJUSTICE of whatever form, from whatever place and to whoever the victim is. This is a worldwide topic that

is witnessed daily in wars and civil wars, in homes, in schools, at work and at personal levels. A case in

point is about mental health issues. This is a closed issue in most societies especially in Africa. That

pressure is mounting on individuals and families to cope with the demands of daily life and shrinking economies,

this taboo subject keeps claiming life's. in my small way I write about it hoping to help one if not two to know

there is help in admitting to the fact that they are overwhelmed and need help.

You are an editor of the magazine Liberated Voices, please tell us about this publication and Womaword?

These two magazines are works of excellence in literary sense and initiatives of the literary activist per

excellence Mbizo Chirasha. He invited me on board because we share the knack of social justice in the broadest terms.

First, Womawords showcases women/girls voices and issues in Africa and beyond. The works and personalities

whose works appear on this platform speak of challenges faced by the wider society but with special emphasis

on women voices. Of course a woman is a human foremost. Her rights are human rights. She is at the center of

the family holding it together and nurturing it for the larger society. In time, I have learnt a great deal

from interacting with these voices that carry the wealth and health of the world. Of special note is the active

involvement of girl child issues in this magazine. A project is in the offing to start a campaign to equip girl

children in difficulty situations with sanitary pads as part of menstrual health initiative which is a part of

the larger mental health issues of our world, especially among the poor and marginalized.

On the other hand, Brave voices Magazine celebrates the success stories of our collective past and present.

It's about men and women who have made a positive influence in diverse fields; from writing, film, leadership,

championing human rights, liberation struggles and those pioneering in the uncharted territories like climate

change initiatives. Only last year, with Mbizo Chirasha on the lead, the members of Brave Voices joined with

fellow Cameroon poet Nsaa Mala to come up with a multilingual poetry anthology that is now in print and available

in book shops and at Amazon. The call was against the genocide against English speaking citizens of the country

vis à viz the French speaking divide. I made some contribution there.

You taught for many years, what did you love about teaching?

True. I taught for many years and I learnt a lot from the many high school students; both in high school and

colleges that taught me so much. The best of the lessons was and continues to be threefold. To be always Alert,

Focused and Organized.

This threefold lesson came very early in my career and at a time of my early adulthood where I could embrace it

with minimal grit.

I must admit that fate sent me to a National school as my first posting after college. In Kenya, National schools

are where the best brains are accepted after primary schools for further education. This crop is talented and easily

understand everything they are taught with ease. They also tended to read ahead of any topic, and sometimes sought

comparative works to better understand whatever they were scheduled to learn. My first stint, armed with lesson notes

and chalk to last forty minutes ended with me gasping for breath from questions seeking examples and giving their

own which I wasn't sure was right or wrong. Let me confess that these forty minutes of a grammar class covering a

topic on the use of past participle had me perspiring and stammering, before the bell saved my shaken demeanor. I

learnt as fast as my learners and forever remained a mile ahead of my wards.

The second lesson was a sense of childish play and adoration of simple joys in life like discussions,

debates, outings, drama and music engagements. Only a young person can truly keep you seeing life through

the lenses of childhood and youth by working with them. I remain grateful to them for these lessons.

What I loved most about teaching is teaching thoughts brought on by words and inference through

literature which awakened the students mind to a deep interaction and love for the written word.

Many years later, when I taught communication skills in college, the nuances of words and how they

affect relationships was something that I carry with me today, though I no longer teach. I can say

for a fact, that the eighteen years were beyond worthy, for I taught and was taught.

What are you working on right now?

I have been working on two books simultaneously for the last three months since lockdown was declared

in Kenya. The first is a book comprising fifteen short stories and a short anthology of poetry; both

riding on the theme of COVID 19.

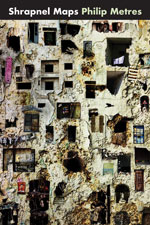

BOOK REVIEW by Miriam O'Neal

Shrapnel Maps by Philip Metres

Copper Canyon Press, 2020

The Kindness In Looking

At first, my first reading of Shrapnel Maps (Copper Canyon Press, 2020, ISBN 978-1-55659-563-9)

left me turning confusedly from grief to anger to a sense of sweetness, and back through the gamut.

Focused on the continuing conflict between Israel and Palestine: as I returned to them, day after day,

I came to accept their shifting emotional ground as necessary-as part of the territory. These are beautifully made,

emotionally difficult poems to read because they insist on the reader's presence as they take us inside of what,

in truth, has become so far, an endless conflict. They visit the tautologies of two histories; inverse claims on

the truth of what this conflict is about and push back, as if to open a common space for breathing. They are poems

of immense compassion that invite a new way to calculate the future for both Palestine and Israel. We discover

unexpected communions in tragedy, but also in human kindness.

It feels necessary to acknowledge that I understand I am an outsider-from a country with its own history of

propaganda, land grabs, water diversions, erasure, racism, etc. I am looking from a distance. Metres' insider

status occurs by way of ancestry, family ties, and years devoted to the pursuit of peace for the Palestinians

and the Israelis. The poems in Shrapnel Maps speak from that devoted pursuit.

The poems' images evoke the tension between visibility and erasure, as when we see Salem Saoody bathing his

little daughter and his niece in a washtub "...their hair slicked/ with soap, their bodies gleaming in

the brisk//delight of being bubble-wet and clean..." in the rubble of what had been his home. Metres'

verbs are visceral: "My flesh has swallowed an entire dream of heaven", "...the apple died, strangled//

by mute trumpets...". "When it rains in Gaza, the tin roofs clatter...". And some images are rendered in

devastating brush strokes, as in "Act Two: This Tide of Blood," which shows us the cadaver recovery

conducted after a bomb blast kills a wedding party. Using reported interviews, we hear a member of the

team speak:

Because someone has to pick up the pieces

of G-d. We get the call & don neon vests

to sort the flesh from flesh. There is a kindness

in looking. To bring even a finger to burial.

Here is a human bomb. Here is a wedding hall.

Now scrape the bride & groom gently from the wall.

.... Something pushes them to do this.

No matter what they have done, each human

in the image of G-d.... (4. AZRIEL, 1-6, 9-10)

The scene is grisly, yet the team member goes about his work with tenderness. His "kindness/ in looking...."

inscribes the poem with sorrow, not just for the victims, but for humanity in that moment-the tragedy that

this is where we are. As I've written this, a female goldfinch, in her drab olive greens, has been perched

on a high branch of the tree outside my window, bedraggled by the Northeast wind and steady rain, but seeming

not in the least befuddled by her circumstances. She is simply where she is. And in the moment it took me to

describe her, she flew away and is, by now, I imagine, perched in another tree. Not a victim in any way, she

is going about her business in the storm. I think again, of the little girls in their tub in the rubble of their

former home, the bridal party destroyed; what would it mean for them to be able to live with storms as the finch does?

Metres' poems are emotionally meteorlogical, historical, communal,

and personal 'maps' of the urge to do more than

survive. Seventy plus years after the State of Israel's formation, as the taking of land from the Palestinians continues,

Shrapnel Maps lays out a cartography that is impossible to read without realizing there are almost no roads out

of this territory that are not fraught with loss, whether you are Israeli or Palestinian-even so, we must try. And there

it is, the sense of the 'we' these poems engender.

Shrapnel is the lasting evidence of an explosion. It shows what as well as who suffered by being near the target.

For Palestinians, the map marks the rubble bulldozers have made where homes once stood, the water tanks intentionally

pierced by bullets, fences that bisect or surround orange groves and olive groves, checkpoints that funnel people from

one unsafe place to another, schools with crumbled facades from rocket strikes, an ice cream factory turned into a

morgue, a drone's record of the heat emanating from a Palestinian woman as she hangs her laundry on a line. For the

Israelis, it is the threat of retaliation, the sense of an enemy who does not sleep. No one escapes unscathed,

and many die.

In "4. Rachel & Ayat" from a sequence titled "Act Three. The Matter of the Flesh of One's Flesh," we hear from a pair

of women, one Israeli, the other Palestinian. Both of them killed in a supermarket in 2003. They speak in unison from

beyond the grave, ".../ at first they could not tell our dark bodies apart. (12-13). And, already I can hear the argument

about who caused whom to die that could be used to identify them, one from the other. Ayat is the bomber. But Metres

doesn't back away from that moment of indistinguishability: two lives ended and nothing gained.

In its forms, Shrapnel Maps is kaleidoscopic; which feels appropriate given the scope of the stories, locations,

and emotions carved out in these pages. Some poems use a cacophony of voices in the form of choruses for 2, 3, or 4 voices,

sometimes telling different stories simultaneously. There are poems in which the words themselves have been blasted apart,

their letters shoved into strange groups that require the reader to pick her way slowly through the alphabetic rubble to

make sense of what is being said, as in "7. CHORUS" from "Act Three...." where the first 5 lines are laid out as follows:

lig ht with outhe at wo rd w ithout le afw ear e

sh ad owsofse l v e s nol ong erlo cke din

bo dies werest in thef old of so met hing

likefur a s hared s kin li nbsp; ght without ey ewords...

wit h out m out h...

light without heat word without leaf we are

shadows of selves no longer locked in

bodies we rest in the fold of something

like fur a shared skin light without eye words

without mouth....

At first, "7. CHORUS" feels like an unnecessary language exercise,

but as the mind becomes accustomed to making

the leaps, sorting out where the white spaces need to go for the words to make sense and the poem to give its message,

an awareness emerges, that this is a mirror of the demands on the hearts and minds of people in a state of constant

siege and loss; the constant regrouping of experiences and the language needed to make meaning out of them.

The challenge to grasp joy from the mouth of grief requires re-collecting the self out of trauma through the vehicle

of language.

Prose poems, erasure poems, sequence poems, persona poems all contribute to the maps. The prose poems and

narrative lyrics mostly focus on the way ideology, religion, and trauma infiltrate ordinary life: children

in a back yard in an American city try to sort out why one family's Orthodoxy prevents them from playing

together or sharing snacks. A lover's preoccupation with the conflict a world away leaves his partner feeling abandoned.

One poem in particular lays out the challenge to respond meaningfully

to this conflict. Aptly titled "[Family],"

this prose poem recounts the moment in a presentation at a College in the United States, about Israel's taking of

Jaffa in 1948. A woman stands up to protest that the presenter is lying, "...this talk is FULL of SPIN.." that in

fact, "the Arabs sold their land, it was too much trouble..." and that the walls are necessary because of

"TERRORISTS." A man then rises to defend the presenter, "The Jews bought a tiny piece of land, but the rest,

the rest was STOLEN..." The shouting goes on as the narrator and other audience members sit silently.

In the end, he tells us, "It goes on like this for a long time. Years, Decades, Generations.

I sit like a child at the table, watch parents grip utensils, spit words like shrapnel. I hate

how I love them.

Ashamed, I look down, unable

to bury the hot metal.

Love and grief and shame are shot through these poems that hunt the heart. We rejoice in communion, look on

with grief, and recognize the shame created by the violence of erasure. The struggle to be visible and known,

to accept and be accepted, to do more than tolerate, pours from this collection. It takes work to remember our

common humanity in the storm of so much division, so much cruelty both intended and unintended. Like an echo of

Auden's, "we must love one another or die" written on the eve of World War II, in his "Afterword" to this collection,

Metres reminds us that we need "to be attentive to the shards of pain, and invite the gentle flowing of kindness" (163)."

With their unflinching gaze and underglaze of care, these poems accept that task.

Raves will be next month.

Cervena Barva Press Staff

Gloria Mindock, Editor & Publisher

Flavia Cosma, International Editor

Helene Cardona, Contributing Editor

Andrey Gritsman, Contributing Editor

Juri Talvet, Contributing Editor

William J. Kelle, Webmaster

Renuka Raghavan, Fiction Reviewer, Publicity

Karen Friedland, Interviewer

Gene Barry, Poetry Reviewer

Miriam O' Neal, Poetry Reviewer

Annie Pluto, Poetry Reviewer

Christopher Reilley, Poetry Reviewer

R. J. Jeffreys, New staff

If you would like to be added to my monthly e-mail newsletter, which gives information on readings,

book signings, contests, workshops, and other related topics...

To subscribe to the newsletter send an email to:

newsletter@cervenabarvapress.com

with "newsletter" or "subscribe" in the subject line.

To unsubscribe from the newsletter send an email to:

unsubscribenewsletter@cervenabarvapress.com

with "unsubscribe" in the subject line.

Index |

Bookstore |

Our Staff |

Image Gallery |

Submissions |

Newsletter |

Readings |

Interviews |

Book Reviews |

Workshops |

Fundraising |

Contact |

Links

Copyright @ 2005-2020 ČERVENÁ BARVA PRESS - All

Rights Reserved

|